The Blue View - The Legend of The Flying Dutchman

/ As a boy, I never tired of reading about sea lore and tales of the sea. Robert Louis Stevenson, Jack London, C. S. Forester, Melville, Richard Dana and Jules Verne were just a few of my favorite authors. One of Marcie's recent blogs mentioned the legend of The Flying Dutchman, which reminded me of an obscure anthology of sea legends I once read. The book was rather cheesy, and I'm sure it never made anyone's best seller list, but it did recount the tale of the ill-fated ship.

I have since read several versions of the legend, but my favorite remains the rendition as told in my old anthology, and is as follows:

As a boy, I never tired of reading about sea lore and tales of the sea. Robert Louis Stevenson, Jack London, C. S. Forester, Melville, Richard Dana and Jules Verne were just a few of my favorite authors. One of Marcie's recent blogs mentioned the legend of The Flying Dutchman, which reminded me of an obscure anthology of sea legends I once read. The book was rather cheesy, and I'm sure it never made anyone's best seller list, but it did recount the tale of the ill-fated ship.

I have since read several versions of the legend, but my favorite remains the rendition as told in my old anthology, and is as follows:

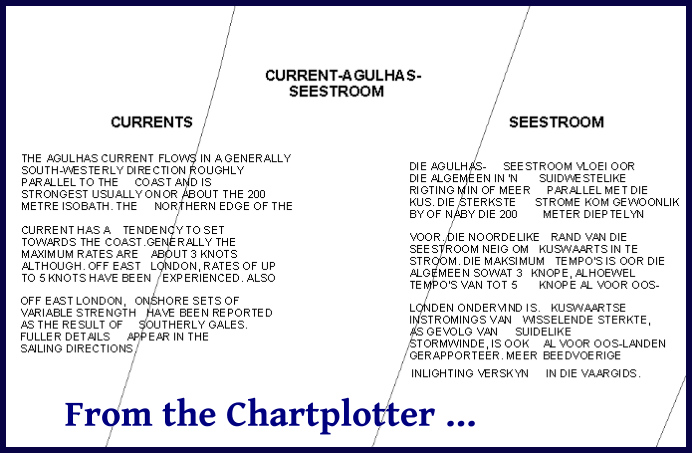

The ship was a Dutch vessel and sailed from Amsterdam in the 1750s. The captain's name was Van der Decken. He was a stubborn seaman, and very strong willed. They were heading around the Cape of Good Hope, but the wind began shifting until it was on the nose and kept growing in strength, and as it did, Van der Decken paced the deck, swearing at the wind. Another vessel signaled that they were heading into Table Bay, and did Van der Decken intend to do the same, whereupon he replied : “May I be eternally damned if I do, though I should beat about here till the day of judgment.” The devil heard his oath and took him up on it, and to this day, Van der Decken on the brig The Flying Dutchman continues to beat around the Cape in the nastiest of weather. The Flying Dutchman is only seen when the weather is, or is soon to become most foul, and is a sure portent of doom and bad luck. In fact, it is believed that a serious accident or death will soon befall the first person aboard to spot the brig. Sightings of the ship report it to be glowing with a ghostly light. Sometimes it is reported that the sails are in tatters, other times sailors say the ship is under full sail and bearing down on them at high speed.

There have been many sightings in the 19th and 20th centuries by other ships, lighthouse keepers and people ashore. One of the more interesting accounts was by Prince George of Wales, the future King George V. He and his older brother, Prince Albert, were on a three year training voyage on a British naval ship. Before dawn on the 11th of July, 1881, the prince's log records:

“July 11th. At 4 a.m. the Flying Dutchman crossed our bows. A strange red light as of a phantom ship all aglow, in the midst of which light the masts, spars and sails of a brig 200 yards distant stood out in strong relief as she came up on the port bow, where also the officer of the watch from the bridge clearly saw her, as did the quarterdeck midshipman, who was sent forward at once to the forecastle; but on arriving there was no vestige nor any sign whatever of any material ship was to be seen either near or right away to the horizon, the night being clear and the sea calm. Thirteen persons altogether saw her ... At 10.45 a.m. the ordinary seaman who had this morning reported the Flying Dutchman fell from the foretopmast crosstrees on to the topgallant forecastle and was smashed to atoms."

The Flying Dutchman has also been depicted in many movies and TV shows: Pirates of the Caribbean, at least two episodes of Rod Sterling's The Twilight Zone, Xena: Warrior Princess, The Simpsons, and even Sponge Bob Square Pants. Based on the genres, I don't think Hollywood is taking the legend seriously.

As for me, a very superstitious sailor, I have no desire to look for portents of foul weather or doom, nor do I want anyone smashed to atoms. Fortunately, knock on wood and thanks to the good graces of Neptune, there were no sightings of the legendary ship by the crew of Nine of Cups when we doubled the Cape of Good Hope.