The Blue View - Working in d' Trini Style

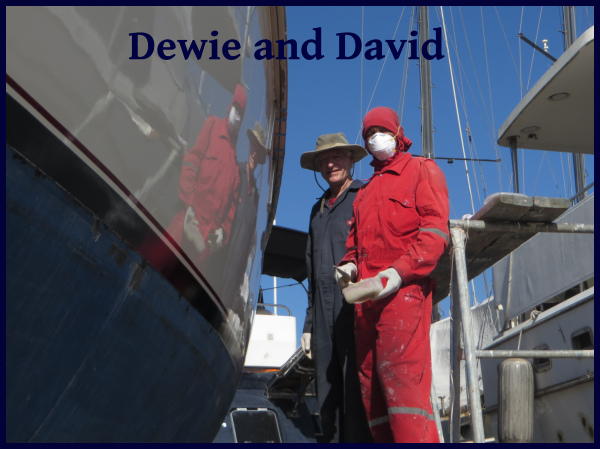

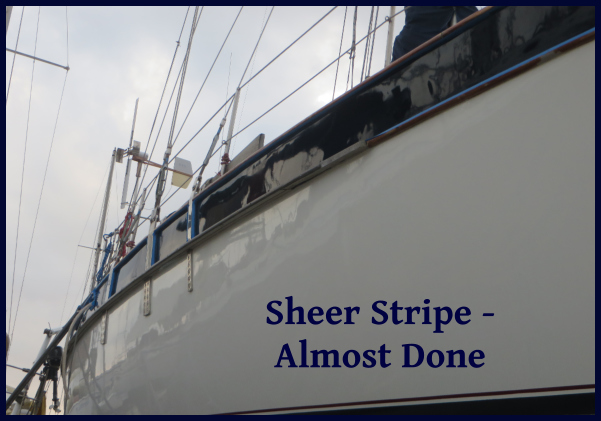

/One of the tasks we wanted to accomplish here was to address some core de-lamination problems in the bulwarks of Nine of Cups. This involved cutting away sections of the fiberglass sheer stripe, removing the old core, replacing it with new marine plywood, embedding everything in epoxy, and re-attaching the fiberglass outer layer. Once this was all done, a layer or two of glass cloth would be applied, then the entire area would be faired and repainted. I did the same to several sections of the deck where our old teak decks had caused de-lamination of the deck core, and while the process took longer than I expected, the end result was a deck that was stronger than new. Since we were on a tight timetable, I thought I'd enlist the help of the Trini guy who had done such a good job painting our hull. To avoid any embarrassment, l'll call him Dewie.

Working with Dewie is both endearing and annoying. To begin with, he repeats everything at least three times, followed by "You unda stand me captn? You hear what ahm sayin?". These last two sentences will be repeated until I verbally acknowledge that I have, indeed, heard and understood him. Now in his defense, he is used to working with us old cruisers. Many of us are hard of hearing and aren't used to the Trini dialect, (nor do they always understand our accents and idioms for that matter) so if something important is being communicated, it is best to make sure everything is being understood. Dewie carries this to the extreme, however. "We work togetta, eh captn... it's easier to clap wit two hands than one. You unda stand me captn? You hear what l'm sayin?" Pause. "You unda stand me captn? You hear what l'm sayin?" . This will be repeated until I respond enthusiastically. If my response is less than enthusiastic, he will inform me that "It a lot easier to work wit someone who enjoy his work and not be in a foul mood all d' time".

Dewie also likes to share his Trini knowledge with me. Some of his tips and "tricks" are well worth knowing. I've learned a lot from the various tradesmen I've encountered around the world, and I try to be open minded and receptive to new ideas. Dewie must think I'm the village idiot, however, and finds it necessary to explain how he does the simplest tasks. When we were setting up a scaffolding to work on the sheer stripe, we needed to round up some additional planks. Dewie informed me that "the captn on dat catamaran is gone for a long time - we can use his planks. Let me show you d' trick for carrying dem. You pick up one end and I pick up d' otter end and we carry it just so. You see my trick? You unda stand me captn? You hear what l'm sayin?" Now if I were to foolishly respond "gee whiz - that is clever...I thought we'd put the planks between our legs and hop over to Cups", all I'd hear for the next hour would be his muttering "It sure is hard working wit someone who always be in d' foul mood."

Dewie was used to working with epoxy, but I knew he had never replaced the core of a deck before. It was important to him that he didn't appear to lack knowledge on the subject, however. "I done dis work plenty of times, captn, but everybody does it diff'rent. How do you like ta do it?". So I explained 'how I like ta do it'. As we were cutting the plywood to fit into the first section of the sheer stripe, I was numbering each piece of wood to make it easier to figure out which piece of ply went where. Dewie insisted this wasn't necessary - "I can figure dis out jus fine when we gluing dem in", so I stopped numbering them. When it was time to place each piece of ply, we had a few miscues, and while we eventually got everything in its place, it took longer than necessary. The next day, Dewie told me he had a little trick to show me. "We should number each piece of timber like so. Dis is how we do it in Trinidad. Dat way, it's easy to figure it out when it time to glue the timbers in. You unda stand mah trick captn? ..." I wish I had thought of that.

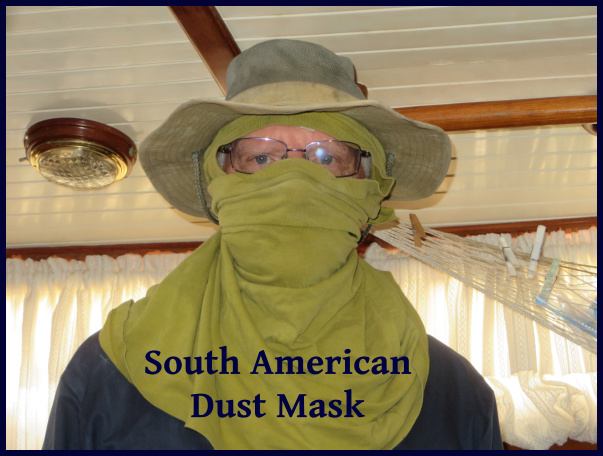

Early on it the process, when we were cutting and grinding the old fiberglass, Dewie came attired in a full Tyvec suit and a respirator. I commented on how I was happy to see he took his health seriously. He said "Yah captn, dat fiberglass is nasty stuff. I try not to bree'd it or any of dem bad chemicals. Mey'be I live to be as old as you, skippah!". I think he was smiling inside his respirator.

Working with Dewie really has been fun and a positive experience. He works hard, always shows up when he says he will, and his work is good, which is more than I can say about most of the guys I've worked with in dozens of other places. His paint work was first rate and we were quite surprised to find it all done on our return to Trini.

Now, if only I can keep from being in d' foul mood all d' day...