The Blue View - When It All Goes Wrong

/Most of our passage from Puerto Rico to St. Augustine was idyllic – a nice broad reach with 15-20 knots of wind, a kindly following sea, warm sunny weather, a 0.5 to 2 knot favorable current, and a full moon to sail by at night. The prop shaft generator and solar panels were producing more power than we needed and nothing major had broken. We couldn't have asked for a more perfect passage – at least for the first six days.

Marcie's blog yesterday talked about how things can quickly change. And when things start going wrong, usually it happens just as the wind picks up, at night and in the middle of the shipping channels – and usually the problems come in multiples. Our first problem was a transmission leak. Without our engine, we could have beat our way to the St. Augustine inlet, but with wind on the nose and the gulf stream current pushing us NE, this would have taken awhile. Then once we arrived, we would have needed a tow to make our way through the narrow, dog-legged inlet – an expensive option. A much better option would be to figure out the transmission problem.

One possibility was the heat exchanger. It is about the size of a half empty roll of paper towels. Sea water is passed through the heat exchanger, and the transmission oil is cooled by pumping it through a coil of tubing that is immersed in the water. Over time, the inner tubing deteriorates and eventually begins leaking. Since the oil is under pressure, it will leak out into the sea water. Usually, once the engine is shut down, sea water will leak back into the tubing, filling the transmission. I wasn't getting seawater into the transmission, but I thought the heat exchanger might still be the culprit. I try to change the heat exchangers every three years, but this one had been in place more than four years and was overdue.

I had a spare, and it took only a few minutes to dig it out. To remove and replace the old one, I had to first remove a shelf in the aft part of the engine room that holds a bin of miscellaneous engine spares as well as my compressor. The rest of the R & R process took about an hour, and all together, the whole thing took maybe 90 minutes for the entire procedure. It went well and without a hitch – always a bad sign.

We topped up the transmission oil and started up the engine. I didn't see anything leaking, so we motored for an hour, then I checked the oil level again. Yikes! It was down another quart. We have three hydraulic hoses connected to the transmission – two that go to the heat exchanger and one that operates the prop shaft brake. With the shelf out I had a better view of the hoses, and I saw a small collection of oil on the hose for the prop brake. I removed it, and sure enough, there was a crack in the underside of one of the fittings.

We could do without the hose if I could figure out a way to plug the hole it was screwed into on the transmission. I rooted around in my various parts bins and finally found a brass hose barb adapter with the right size male thread. Using a bolt, nut and copious amounts of Permatex Gasket Maker (the type impervious to transmission and engine oil), I made a plug for the hole that would withstand the pressure. I screwed it into place, topped up the oil, and we motored for another hour. When I checked the oil level again, the good news was that the oil level seemed to be holding. The bad news was that the engine room was awash in seawater. While I was trying to figure out where it was coming from, the high water bilge alarm went off.

There is an old adage that there is no better bilge pump than a panicked sailor with a bucket. While we weren't quite at the panic level, it was obvious we needed to handle the problem. I closed all the seacocks that could possibly be feeding water into the engine room then we turned on both electric bilge pumps, Marcie began pumping the manual bilge pump, and I worked at bailing out the engine room. Even so, we were barely keeping up with the water ingress. Where the hell was all that water coming from?

Then I spotted the culprit. The prop shaft seal, which is located well aft of the engine room, has a vent hose that should be led up above the water line. I had routed it to the top of the engine room and secured it in place with cable ties. Apparently, when I removed the shelf, I inadvertently pulled it loose from the cable ties. It stayed in place for awhile, but the vibration from the engine caused it to slide down and the end eventually came to rest on the engine room floor – well below the waterline. It was a quick fix to put it back where it belonged, and this time I made sure it could never come loose again.

It took another half hour to pump out all the water and clear the engine room. After checking everything one last time, we were on our way. We checked the transmission oil every hour for several hours, and it was no longer losing oil.

What I took away from all this was that while it was nice to be able to find and repair the transmission leak problem, I am most embarrassed that I didn't properly secure the vent line, causing an emergency situation.

Looking at the bright side, we did get to test the high water bilge alarm and all three bilge pumps, which, happily, all worked.

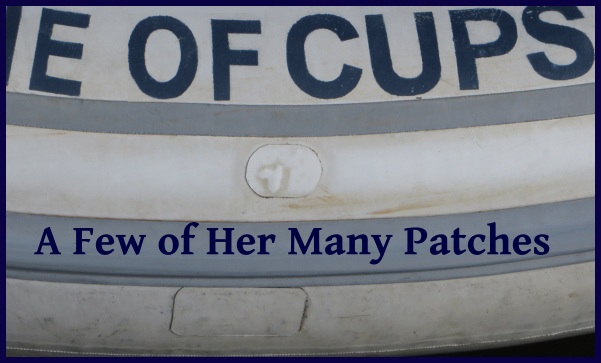

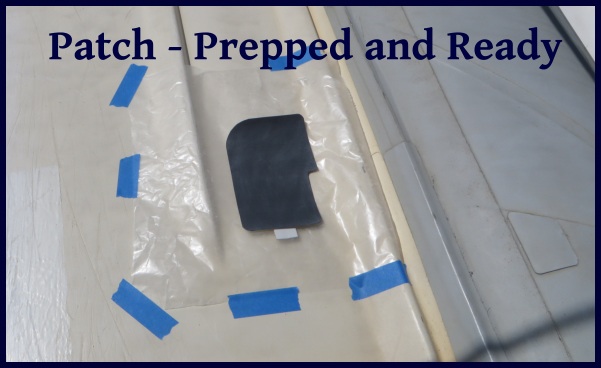

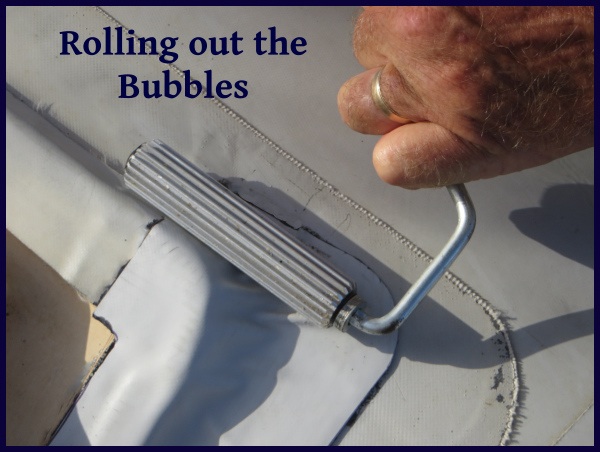

Our venerable dinghy is well into her ninth year aboard Nine of Cups. She's seen a lot of nice soft sand beaches, but she's also seen her share of barnacle encrusted, concrete jetties, rocky shores and coral reefs. On several occasions, she's gotten roughed up by an amorous fisherman's panga as well. Maybe it's her full-bodied figure or her soft sides that attract these rough characters, or maybe she just likes 'bad boys', but they always seem drawn to her and vice versa. Nine years of the sun's UV rays have also taken their toll. She's made of hypalon material, which is more resistant to UV damage than PVC, but not impervious to the sun's effects.

Our venerable dinghy is well into her ninth year aboard Nine of Cups. She's seen a lot of nice soft sand beaches, but she's also seen her share of barnacle encrusted, concrete jetties, rocky shores and coral reefs. On several occasions, she's gotten roughed up by an amorous fisherman's panga as well. Maybe it's her full-bodied figure or her soft sides that attract these rough characters, or maybe she just likes 'bad boys', but they always seem drawn to her and vice versa. Nine years of the sun's UV rays have also taken their toll. She's made of hypalon material, which is more resistant to UV damage than PVC, but not impervious to the sun's effects.