The Blue View - Anchor Swivels

/ An anchor swivel is often used to attach the anchor to the end of the chain. I say often, because not everyone sees any advantage to using a swivel.

An anchor swivel is often used to attach the anchor to the end of the chain. I say often, because not everyone sees any advantage to using a swivel.

The purpose of an anchor swivel is to prevent the anchor rode from twisting excessively. If a boat is anchored for a long period of time in an area of large tidal and/or wind changes, it’s possible that it will do a complete 360 degree swing once or twice a day. Eventually, the rode could twist enough to unlay a 3-strand rope rode or put enough twist into a chain rode to introduce torque stress on the chain and shackles. The twists may also cause a chain rode to bind up and jam a windlass gypsy.

There are potential problems with several swivel designs, however. Some swivels are weaker than the ground tackle for which they are designed. Some are subject to internal corrosion and cannot be easily inspected. Others have no way of seizing the pins and/or bolts, introducing the possibility of the swivel coming apart while in use.

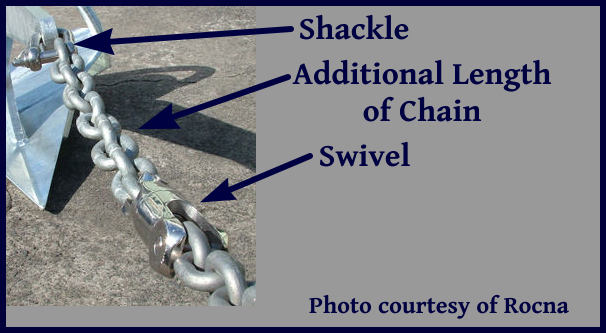

Additionally, some swivels can be damaged or weakened if the pull is side-to-side rather than along the axis of the anchor. The Rocna website suggests adding a short length of chain between the swivel and the anchor shackle to eliminate this problem. On Nine of Cups, however, there isn’t enough distance between the anchor shank and the windlass to add chain between the swivel and the anchor.

In our view, we’ve always thought the risks introduced by adding a swivel outweighed the benefits. While we’ve certainly had the occasional problem in the thousands of times we’ve dropped the hook, none that I recall was due to the lack of a swivel. We do have a heavy bronze bow roller with a groove in it that prevents any twists in the chain from making their way to and jamming the gypsy, and this no doubt helps. And perhaps we’ve never been anchored anywhere long enough in the type of conditions that would introduce sufficient twists in the rode to cause a problem. The only issue – and it is more of an inconvenience than a real problem – is that our anchor sometimes comes out of the water with the flukes facing forward, but this is usually corrected by dipping it back into the water while the boat is moving or by rotating the anchor with a boathook. At any rate, I’m not convinced that a swivel will prevent this.

I like to keep an open mind about new ideas, however, and at a recent boat show I saw a new swivel, made by Mantus, that seems to have overcome all my objections. My first impression was that it’s a very large hunk of 316 stainless steel. It not only looks strong, but the manufacturer’s specs indicate that it is stronger than the 3/8 HT chain we use. It is easily dismantled for inspection, and all the pins are oversized and can be seized. Finally, the business end that attaches to the anchor is terminated in a large shackle, making it unlikely to have problems with side-to-side pulls. Mantus was offering it at a discounted show price with free shipping, and in the interest of keeping myself informed, I bought one.

We’ll be returning to Cups in a little over a week, and I plan to install it then. I’ll keep you posted on my thoughts, good and bad, as it gets used.

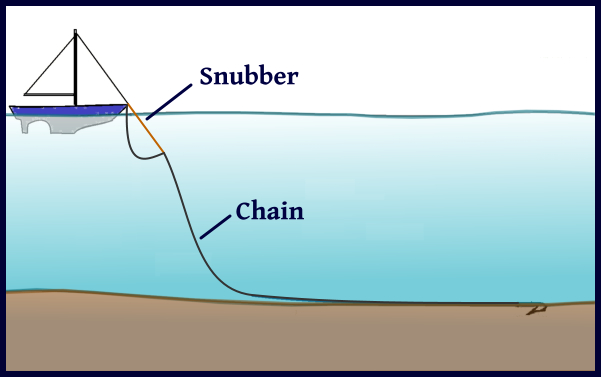

Nine of Cups has all chain rode, and we never anchor without using a snubber. This is a stretchy nylon line attached between a strong point on the boat and the anchor chain. In strong winds, the anchor chain will stretch out almost straight, and as the wind and waves cause the boat to buck and jerk, there is no give in the chain, causing tremendous stress on the boat - not a good thing. Even worse, the sudden jerks on the anchor can cause it to break free from the bottom – even less of a good thing. The elasticity of the rope snubber reduces the sudden tugs on the anchor and the stress on the windlass and chain stopper.

Nine of Cups has all chain rode, and we never anchor without using a snubber. This is a stretchy nylon line attached between a strong point on the boat and the anchor chain. In strong winds, the anchor chain will stretch out almost straight, and as the wind and waves cause the boat to buck and jerk, there is no give in the chain, causing tremendous stress on the boat - not a good thing. Even worse, the sudden jerks on the anchor can cause it to break free from the bottom – even less of a good thing. The elasticity of the rope snubber reduces the sudden tugs on the anchor and the stress on the windlass and chain stopper.