FAQ - Do you worry about ciguatera (fish poisoning)?

/We've been asked several times about ciguatera poisoning, how to avoid it and what happens if you get it. We've never had ciguatera (cross our fingers) and tend to avoid any fresh fish caught in reef areas. With that in mind though, a cruising friend bought some fresh fish at a market in Vanuatu and was deathly ill with it. Luckily, our good friend and naturopathic physician, Alan Profke, was in the anchorage at the time and was able to treat Isolde and help her recuperate. So, when yet another person asked us about ciguatera, it only seemed logical to ask Alan if he'd help out with a bit more advice and write up something that might benefit all the cruisers out there.

CIGUATERA POISONING. POISON FIS. (POISON FISH IN BISLAMA)

by Dr Alan Profke ND

At the request of the Nine of Cups crew, I was asked to provide some information to assist yachtsmen and women in the treating of ciguatera. I hope this helps.

What is Ciguatera?

The first recorded case of ciguatera fish poisoning was noted in 1774 in the logs of Captain Cooks' ship, the HMS Resolution. Captain James Cook himself suffered with this malady twice whilst in the New Hebrides, or Vanuatu as it is now known. The toxins that produce ciguatera come from a group of organisms called dinoflagellates that proliferate in tropical and subtropical waters. Dinoflagellates adhere to coral, algae, and seaweed where they are eaten by herbivorous fish who are in turn eaten by larger fish and so on. The larger the fish, the more toxin that can accumulate in its flesh. Gamberdiscus toxicus is the primary dinoflagellate responsible for the production of a number of toxins that bring on ciguatera. The toxins are known as ciguatoxin, palytoxin, maitotoxin, and scaritoxin. Ciguatera is odourless, tasteless and heat resistant, so the toxin cannot be eliminated by cooking.

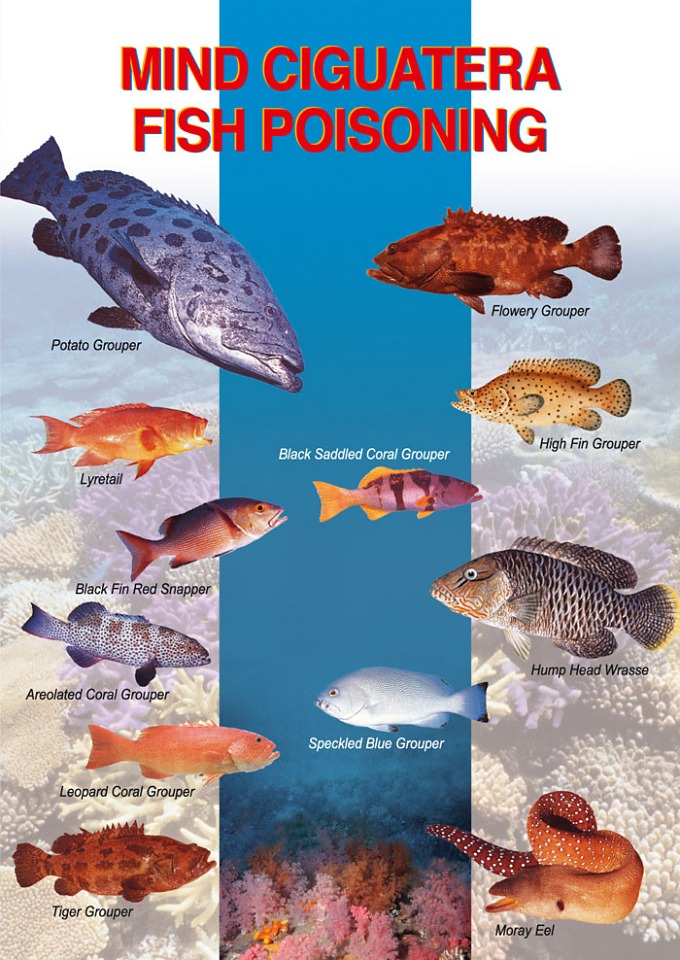

Which fish carry ciguatera?

The fish that affected Captain Cook was thought to be a red bass, however there are many fish that carry the toxins. In fact, up to 400 species of reef fish have been identified so far that are affected by these toxins. The fish that are most likely to be affected are RED BASS, WRASSE, TRIGGER FISH, SNAPPER, SPANISH MACKEREL, QUEEN FISH, MORAY EELS, CORAL TROUT, BARRACUDAS, PARROT FISH,GROUPERS, AND AMBERJACK. Predator species are the worst affected, but other fish can carry the toxins as well.

Symptoms of Poisoning

The symptoms of ciguatera poisoning range from mild to severe and can be evident within one hour or can take up to 24 hours or more to start showing their effects. The symptoms can last for weeks, or in more severe cases, can take months or even years to finally be gone. In some cases, the poisoning has led to long term disability, but this is not generally the norm. Patients can recover and then have relapses. Many patients that have had severe cases of fish poisoning have told me of repeated symptoms months or years later after eating fish, even when the fish has not affected anyone else who has eaten it. There seems to be an association between the consumption of fish and the development of perceived symptoms even when the fish appears to be "toxin free". It has been reported that symptoms can also be triggered by nuts, seeds, alcohol, products containing fish, chicken, eggs and even exposure to bleach and other chemicals. Exercise can also trigger symptoms to surface. This, I have only found in the worst cases.

The major symptoms in humans are gastrointestinal and neurological. Nausea, vomiting, cramping in the abdomen, metallic taste, aching teeth, and diarrhea are often followed by neurological symptoms, such as headaches, myalgia (muscle aches), paraesthesia, numbness, vertigo, hallucinations and ataxia. Excessive sweating may be the first sign, however tingling or altered sensation around the lips, mouth, tongue and throat are the most common first signs. There may be numbness, tingling or extreme sensitivity or even reversed feelings of heat and cold. It has been reported that healthy partners of a ciguatera-affected person can suffer some of the symptoms after sexual intercourse, signifying that the toxin may be transmitted sexually as well. Facial rashes and diarrhea have been reported in infants being breastfed when the mother has been poisoned, so this may be another route for secondary poisoning. In the most severe cases, breathing can be affected, so the person who is affected needs to be monitored closely.

How do I know if a fish is poisoned?

First of all, when you are near an island check with the locals. They will usually know if the fish are safe to eat or not. They may point out certain areas that are affected, so the advice is steer clear of fishing in that area or even close to it.

There have been many suggestions made and theories put forth as to how one can tell if a fish is affected or not. I will list some of these here, but must stress that none of these is scientifically validated.

- Take a tiny piece of the raw fish flesh and hold it in your mouth, preferably under your tongue. If you perceive any numbness or a tingling sensation, then ditch the fish.

- If you have any tingling, numbness or a stinging sensation on your hands or skin whilst filleting the fish, ditch it. You obviously need to have the raw flesh of the fish make contact with your skin to have this occur, so if you wear gloves when filleting, remove them.

- Flies will not touch the fish.

- Cats will not touch the flesh. This one I know personally is incorrect having lost my dearly loved moggie on a trip to the Great Barrier Reef. The toxin affected him within two hours and despite our most heroic efforts to save him, he died shortly thereafter. He had eaten part of the liver of a mackerel that I had filleted.

- Try putting a piece of fish on the ground to see if the ants will touch it. If ants continue to walk on the fish and not die, then it is considered safe.

None of these methods has any scientific validity, so I would not place a lot of faith in any of them. I personally use the sub-lingual method and to date have not suffered any effects of ciguatera. Note that I have ditched a few fish along the way that I suspected of being poisoned.

How do I treat ciguatera poisoning?

I list the following points to assist cruisers who may be exposed to ciguatera and those providing care.

First of all, it is important to monitor the patient carefully and to treat the patient both symptomatically, as well as assisting the body to detoxify the ingested toxin. It is vitally important that the affected person be resting and drink absolutely no alcohol. Keep up fluids by drinking filtered water. I also use Vitamin C, preferably in a powdered form with Bioflavenoids. In the first stages of poisoning, take 1/4 teaspoon (500 mg) in water, ingested three times per day. Make sure the patient continues to take Vitamin C, even after improvement is noted. The dosage can slowly be reduced, i.e. take 1/4 teaspoon three times per day for a week and then 1/4 teaspoon twice daily for a week and then 1/4 teaspoon once a day for a month before discontinuing.

It is also vitally important to keep the bowels open, so one should expect to move ones bowels once or twice per day. Stay away from highly salted and sweet foods. I recommend probiotics. These must be a good species. Many probiotics today are just sold for commercial reasons and are not very effective. I personally use a product from the USA called Trenev Trio or Healthy Trinity (Natren is the company in the US). In the first stages, take one capsule before morning and evening meals and, as you improve, reduce to one capsule only before the evening meal.

Liver support is vitally important, so in this regard, I use a homeopathic medication from a company called Heel (Germany). The product is called Hepeel and I recommend one tablet sucked sub-lingually before meals. This is very effective for treating the nausea and assisting both phase 1 and 2 in detoxifying of these toxins.

To treat the diarrhea, I use Saccharomyces Boulardi. This is available in 250 mg capsules and can be used in the acute phase at two capsules, three times per day. Again, as you improve, lessen the dose to one capsule three times per day and then down to one capsule twice per day until totally recovered.

Calcium channel blocker drugs have been used to reduce the severity of the symptoms of ciguatera. Magnesium is a natural calcium channel blocker, so can be added to the Vitamin C. It is imperative that the magnesium is either a citrate or a diglycinate, so as not to exacerbate the diarrhea. In a powdered form, take 1/4 teaspoon along with the Vitamin C.

All of the above doses are for human beings 12 years of age or older. Children from 5 years of age to 12 years of age should be administered half that dose. In the case of the homeopathic medicines recommended, you can break the tablet into two.

A drug called Questran has also been used to assist in ridding the body of ciguatera toxins. This drug combines with bile acids and prevents them being reabsorbed, thereby excreting the toxin through the bowel movement. A good liver support that assists phase one and two detoxification is vital along with the probiotics that assist bowel detoxification. I personally will not use Paracetamol as this can have a negative effect on liver detoxification, and so, would recommend Ibuprofen for pain relief, if this can be tolerated.

In closing...

In closing, I must say that it is my belief that the more healthy a body is and the better the body is at detoxifying substances which is largely dependent on liver and gut health, the better the body will handle exposure to ciguatera toxin as with any other toxin to which you may be exposed.. To that end, I always suggest a least a good daily multi-vitamin that contains high doses of Vitamin B along with a good probiotic and a healthy diet.

Many cruising yachties do ocean passages and suffer sleep deprivation and, in some cases, dehydration . This can have a devastating effect on the immune system. To assist the body in its recovery and to support good health, the minimum I would suggest would be the good multi-vitamin and a probiotic. In my clinic in Australia, I seldom see ciguatera, but I often see it in Vanuatu where I also have a clinic. I have had very good results using the above to assist the many native patients I see on our island home and some of the cruisers who visit us from time to time. Without a doubt, the best way to handle ciguatera poisoning is to avoid it.

I wish you Fair Winds and Following Seas.

Dr. Alan Profke. ND. Naturopathic Physician

Brisbane, Australia and Aore Island, Vanuatu