Blue View – Choosing the Right Boat

/Calculating Boat Parameters

To state the obvious, choosing the right boat depends on the kind of sailing you plan to do. The right boat for weekend races at the yacht club won't necessarily be the best for the weekend gunk-holer, nor the coastal sailor and certainly won't be the preferred boat for a world girdling ocean sailor. What I plan to do is compile some thoughts to consider when searching for a cruising boat, whether the plan is to explore the Bahamas for a year or two or sail off around the world. The first part will be some of the technical considerations – how big, how wide, how heavy is the ideal boat. In the second part, I'll talk about systems to consider like tankage, engine, stoves, etc. Then I'll talk about the things that you may want to add – solar, diesel generators, wind generators, etc.

Boat Size. One important criteria is boat size. Bigger is better in some things, but not always with sailboats. A rule of thumb with boats is that the price doubles for every 10 feet of length. That's not just the cost of the boat, but also the cost of everything onboard. A 45 foot boat costs about twice what a similar 35 foot boat costs, and so do the costs of replacing the lines, sails, winches, and canvas. Bigger pumps and larger autopilots are needed. Marina fees, haulout costs, the amount of paint for the bottom – everything costs more for a bigger boat.

The point is not to lose sight of the big picture. If you can afford a big boat, go for it, but there are lots of good, seaworthy, smaller boats out there, very reasonably priced. If buying a bigger boat means postponing the retirement date by five years, or reducing that cruising sabbatical from three years to one, it might be better to go with a smaller boat. Most of the famous cruising couples of the latter part of the last century did just fine on much shorter sailboats.

Another issue with big boats is – well, the size of everything. Nine of Cups, at 45 feet, is about as big a boat as we feel comfortable handling by ourselves, or by either of us, for that matter, if one of us was injured or sick. Even if we were to lose all electrical power, we can still hoist, trim and reef the sails, and if need be, raise and lower the anchor by hand. As long as our rig and sails remain intact and Nine of Cups remains seaworthy, either of us can still sail her to the next port. Much bigger, and we'd need electric or hydraulic winches and furlers.

Beamy vs. Skinny. Most boats spend the majority of their time either anchored or tied up at a marina. A boat with a bigger beam has more liveaboard space, and more interior volume translates to a more comfortable liveaboard boat. On the other hand, a less beamy boat has a better windward performance in rough conditions, handles better and is more sea kindly. The usual measure of how beamy a boat is uses the ratio of the length to the beam. The Length-to-Beam ratio or LBR is usually calculated by dividing the waterline length (LWL) by the waterline beam (BWL). If the BWL isn't specified, an approximation can be used by using 0.9 x the maximum beam (Bmax). Recommended LBR for a good sea kindly vessel: 3.0 or higher. Nine of Cups has an LBR of 3.47.

Draft. All things being equal, a skinny boat will heel more when sailing to wind than a beamy boat. To counter this, designers try to add more weight down low. Some of the narrow racing boats we've seen have 12' or even 14' fin keels with a large lead bulb attached to the end. That's not real practical for a cruising boat, however. A 6' draft seems to be a good compromise. Cups has a draft of just under 7 feet, a bit more than we wanted, but other than much of the Bahamas and portions of the ICW, there haven't been that many places where the extra foot made all that much difference. If you plan to do a lot of cruising in the Bahamas, you might want to consider a shoal draft vessel.

Cruising Displacement. The displacement or displacement tonnage of a vessel is the vessel's weight. The name reflects the fact that it is measured indirectly, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the boat, and then calculating the weight of that water. The displacement quoted by the manufacturer can be quite misleading. A cruising boat set up for a long ocean passage will weigh considerably more after loading her down with diesel, water, provisions, tools, books, spares, extra anchors and chain, and propane. These extras can easily add up to thousands of pounds. Adding a couple thousand pounds to a light displacement vessel will affect its performance much more significantly than the same weight added to a heavy displacement boat. When calculating the various parameters below, you will get a more accurate picture of the vessel's likely performance if you start with the manufacturer's displacement and add the estimated weight of the gear you will be adding for the type of cruising you will be doing.

Comfort Factor. Ocean racers like to go fast, no matter how uncomfortable the ride. While we like to maintain a reasonable speed, we much prefer not getting beaten up, nor getting any more seasick than absolutely necessary on a long passage. Ted Brewer, one of America's foremost boat designers came up with a “motion comfort factor” that estimates how comfortable a boat will be when the going gets rough: Comfort Factor = Displacement(lbs) / (0.65 x ( 0.7 x LWL + 0.31 x LOA) x Beam1.33 ), where the higher the number, the better the ride – and often the slower the boat. For Cups, this would be as follows: CF = 31000/(0.65 x ( 0.7 x 40.33 + 0.31 x 45.67) x 12.891.33) = 31000/825.7 = 37.5. Typically, a small racing boat would have a CF under 20, a light displacement cruiser would have a CF between 20 and 30, a moderate displacement cruiser between 30 and 40, and anything higher would indicate a heavy displacement cruiser.

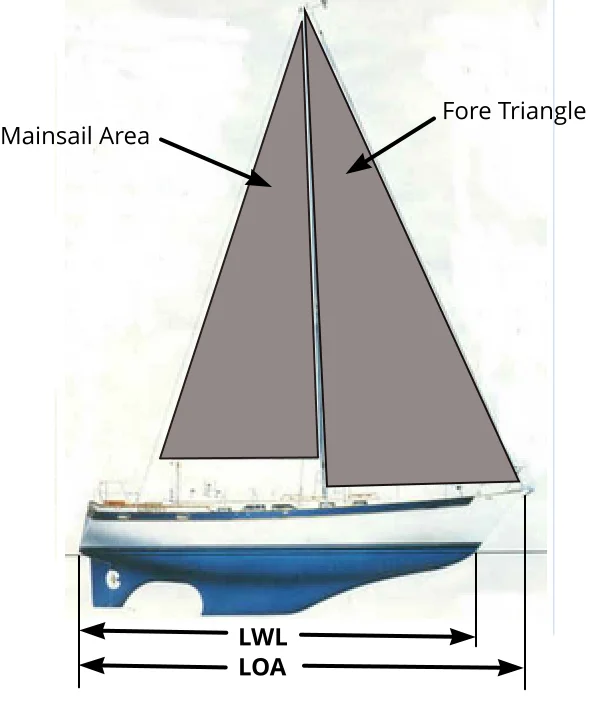

Sail Area-Displacement Ratio. A heavy displacement boat will often be a slow one unless the sail area is increased proportionately. If the boat has enough sail to compensate for the extra weight and is stiff enough to handle the sail area, it can perform quite well. The Sail Area- Displacement Ratio (SADR) is calculated by adding the mainsail area and the foretriangle area and dividing by the displacement in cubic feet raised to the 2/3 power. Since seawater weighs 64 lbs/cubic foot, the displacement in cubic feet can be calculated by dividing the displacement in pounds by 64. For Cups, this worked out to be: SADR = (356Ft2 + 509Ft2 )/(31000\64)0.667 = 14.0. If the staysail is added in, this becomes 17.1. An SADR between 15 to 16 is considered reasonable for a cruising boat, 17 to 19 is typical for a performance cruiser, and 20 to 22 is on the high side.

Displacement – Length Ratio. This ratio provides an idea of the load carrying ability of a boat. The higher the DLR, the less all that added weight will affect the boats performance. It is calculated as follows: DLR = displacement in long tons/(0.01 x LWL)3, where a long ton = 2,240 pounds. Lightweight boats are usually in the 100 to 200 range, most cruising boats are in the 250 to 400 range, and some heavy displacement boats are above 400. Using the manufacturer's displacement number, Cups comes in with a DLR of 275.

Enough with all the technical aspects of boat buying. When we were searching for our perfect boat, I reviewed the specs on a number of boat makes and models and came up with my short list of candidates. Marcie added her criteria on the things she felt were important to her, which narrowed the list further. Then we began looking at all the candidates. It was a long process – most of the boats weren't quite what we wanted, and we weren't ready to compromise.

I'd like to say Cups was one of the candidates that we found after all our painstaking research, but in all honesty, it wasn't that way at all. We made a trip to Kemah, TX. to look at a Hans Christian Christina there, but weren't impressed. Our broker said that as long as we were there, we might want to look at another boat, a Liberty 458. A Liberty 458? That was not only not on our list of candidates, but wasn't even a boat we'd ever heard of. We took one look, however, and knew the sailboat, now known as Nine of Cups, was the boat for us. She was beautiful! A little bigger and with a deeper draft than we were looking for, but still, we knew she was the one.

I did go through the motions of checking the technical specifications of Cups, but I suspect that unless the numbers came out totally absurd, the results wouldn't have swayed our decision. As it turned out, Cups' numbers weren't bad, and after more than 17 years aboard, I can say we've never regretted our decision.

So, this demonstrates how important an engineering approach is to the decision making process, and how not to let emotions get in the way. If I hadn't done all that number crunching and analysis, we wouldn't have been in Kemah looking at the Christina, and might not have found Cups.

Blue View - Choosing the Right Rig