Blue View - The Amazing U.S. Life Saving Service

/“The regulations say you have to go out, but you don’t have to come back.”

… unofficial motto of the U.S. Life Saving Service

Marcie’s last blog talked about visiting the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Whitefish Point, Michigan. It was sad and sobering to read the accounts of a few of the hundreds of ships lost just in Lake Superior. Drowning in freezing water is not a way I’d choose to go. Most were lost before the advent of modern electronics and weather forecasts. Radar and AIS systems now prevent collisions in the densest of fogs; GPS navigation ascertains the vessel’s location no matter how bad the weather; and precise weather forecasts enable ships to avoid the worst of oncoming storms. That doesn’t mean vessels don’t still sink… when we were crossing oceans on Nine of Cups, more than a few of our friends and acquaintances were lost at sea. Sometimes it was due to poor judgment, but just as often, it was just bad luck or being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Of particular interest at the museum was the building devoted to the U.S. Lifesaving Service. We’ve visited other museums devoted to the Lifesaving Service, notably in Nantucket and Provincetown, and were always gobsmacked at the tales of heroism exhibited by these men.

A little history…

The first lifeboat station was built in Cohasset, Massachusetts in 1807 by the Massachusetts Humane Society. The station had a 30-foot, cork-lined lifeboat and a crew of six to eight. They continued to build more stations along the Massachusetts coastal areas, as did other coastal communities.

The federal government also began building stations in New Jersey in 1848. These were small buildings equipped with surf boats, Lyle guns and other life saving equipment, and were administered by the newly formed United States Revenue Cutter Service. It was up to the local community to provide the volunteer crew - much like a volunteer fire department.

Most of these stations, however, were located near harbor entrances, leaving large areas of the coast unprotected. In addition, many of the crews were poorly trained. This was most evident when a category four hurricane swept up the East Coast in September of 1854, causing the deaths of many sailors and fishermen.

In 1871, Congress allocated the money to build a network of life saving stations with paid, trained, professional crews. These were organized into the U.S. Life Saving Service in 1878, administered by the Treasury Department.

Replica of an 1800s lifeboat

When a shipwreck occurred, their job was to portage the lifeboat and other gear as near to the troubled vessel as possible. The first thing that was tried if the vessel was near shore was the Lyle gun - a small cannon with a cast iron projectile. An eye bolt was screwed into the end of the projectile, and a light rope was attached to the eye bolt. When the canon was fired, the projectile and the trailing line would, hopefully, pass over the vessel, dropping the line on deck. The small line was attached to a much heavier line and pulley, and the crewmen aboard the vessel would use the light line to haul the heavier line aboard, then secure it to the ship. The line was tensioned and anchored ashore, and the pulley system was used to transport the passengers and crew to shore, one at a time. The biggest limitation was the range of the Lyle gun. Under ideal conditions, it had a maximum range of 2100 feet, but the actual distance was much less when firing into the wind, rain and/or snow. It also depended on there being able-bodied, uninjured crew aboard.

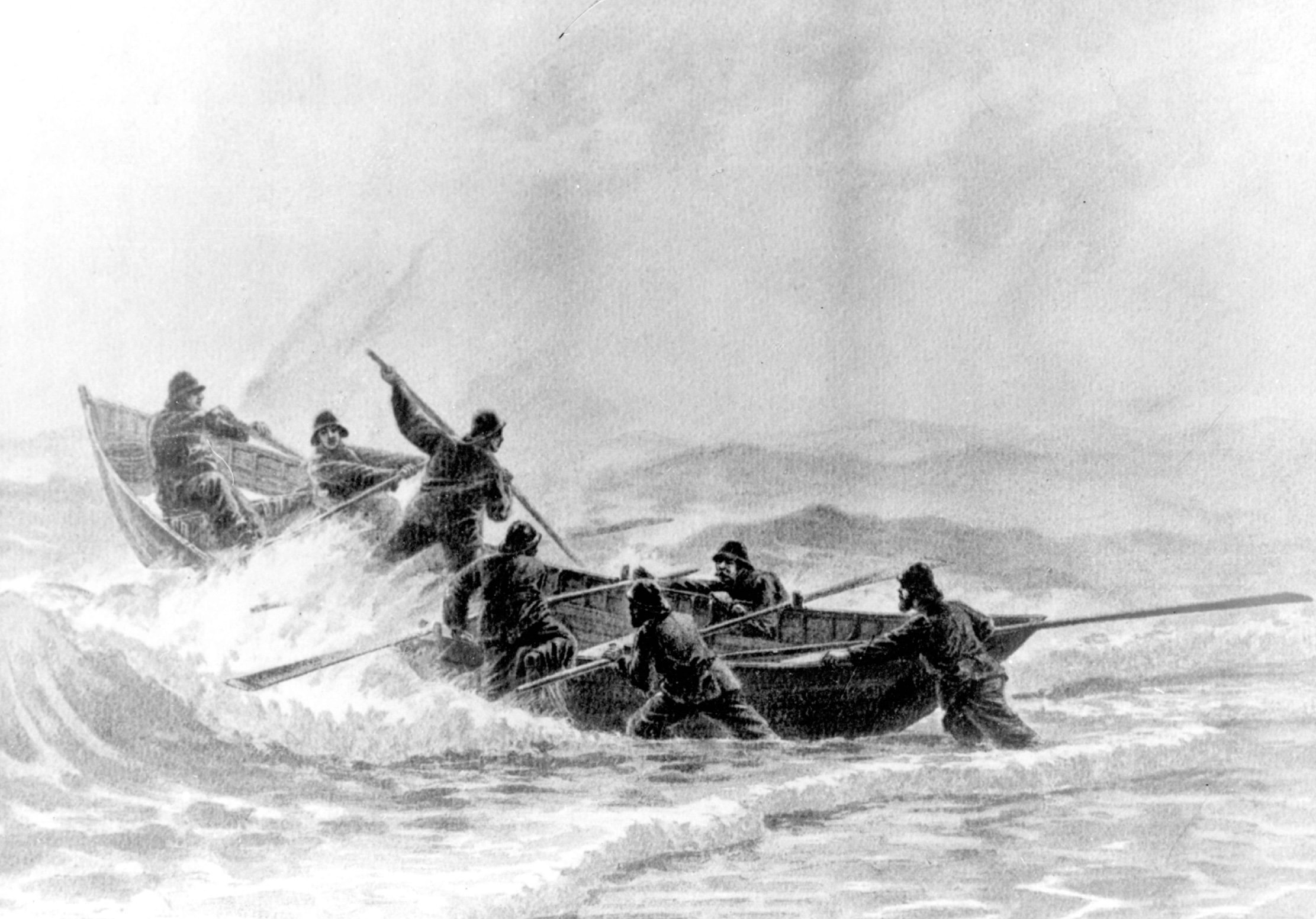

If the Lyle gun wasn’t successful, the only other option was to launch the life boat, row out to the ship, and rescue the crew. On a calm, sunny day, this would be a simple job, but wrecks rarely happened in settled weather… they usually occurred, of course, in the middle of a storm, with a huge surf, horizontal, freezing rain, and immense winds. Marcie and I once explored a beautiful, uninhabited island off the coast of Chile, Isla Damas, which was known for its Humbolt penguins. When we landed our inflatable dinghy, the surf was benign, but while we were exploring the island, the wind began increasing, and with it, the surf. We had a heck of a time launching the dinghy. The surf swamped us twice, nearly capsized us once and washed us back ashore at least a dozen times. This was only a moderate surf… I can only imagine how much more difficult and dangerous it would be for the life saving crews attempting to launch their lifeboat into a freezing, raging surf. They didn’t have the option of deciding that the conditions were too bad and staying ashore. The regulations and their duty required them to launch the lifeboat and attempt the rescue. Thus their unofficial motto, “The regulations say you have to go out, but you don’t have to come back.”

We read many, many stories of the heroism shown and the hardships endured by the members of the life saving service. Here’s one:

In 1886, Albert Ochoa and his crew received a telegram that two large ships had foundered and were in danger of sinking with all hands… 110 miles away. With the assistance of the Ontonogan Railroad, he loaded his boat, gear and crew aboard a train, and despite a raging blizzard, made the trip in three hours. There he transported the lifeboat and Lyle gun to the wreck site, and set up the gun. He successfully got the line to one of the ships, but apparently the crew was too weak or too demoralized to venture out and secure the line. Captain Ochoa then attempted to launch the boat. It was capsized twice, swamped three times and nearly broken up on the rocks, but he persisted and eventually made it to the first ship. His lifeboat was so iced up by then, he could only take nine crewmen at a time, however, so he had to land and launch the boat twice more. In the end, he saved all 24 crewmen aboard the two ships. Eleven months later, he repeated the feat, this time saving ten people aboard the schooner Alva Bradley.

Unfortunately, his story has a particularly sad ending. While in charge of another life saving station at Eagle Harbor, he died of pneumonia, which was quite likely work induced. There were no death benefits, and his twelve orphaned children were left too destitute to pay for a headstone. After all those lives he saved at great personal risk; after all the hardships he endured; he was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in Eagle Harbor Cemetery.

Some Statistics:

In 1915, President Wilson merged the Life Saving Service with the Revenue Cutter Service to form the U.S. Coast Guard. By then there were more than 270 stations covering the Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf coasts as well as the Great Lakes. During its 44 years, the Life Saving Service accomplished the following:

Vessels assisted - 28,121

Persons rescued - 178,741

Shipwreck victims lost - 1,455

Lifesavers that perished in the line of duty - 177

That tradition continues with the Coast Guard, whose heroic helicopter crews, ship’s crews and dauntless rescue swimmers routinely risk their lives saving others.