The Topaz Internment Camp

/My first job out of university was as a design engineer at the University of Colorado Medical Center. It was a fantastic job. When a medical researcher needed a gizmo for his research project… maybe an interface to convert the data from some esoteric instrument like a plethysmograph to a format his computer could read, or perhaps an implantable device that measured and transmitted aortic blood pressure, I was the guy who got to design and build it.

One of my colleagues was another young engineer named Ralph Nakamoto, and we got to be quite good friends. He shared with me the appalling story of what happened to his parents, both natural born Japanese American citizens of the U.S., during World War II. They had lived all their lives in San Francisco and owned a small grocery store. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, in order to mitigate a security risk which Japanese Americans were believed to pose, President Roosevelt issued an executive order that forcibly relocated and incarcerated more than 120,000 people of Japanese descent, of which about 80,000 were U.S. citizens, to “relocation” camps, which were little more than barbed wire enclosed concentration camps. The rest were Issei (first generation) who were subject to internment under the Enemy Aliens Act. Many of these "resident aliens" had been inhabitants of the United States for decades, but had been deprived by law of being able to become naturalized citizens. Also part of the West Coast removal were 101 children of Japanese descent taken from orphanages and foster homes.

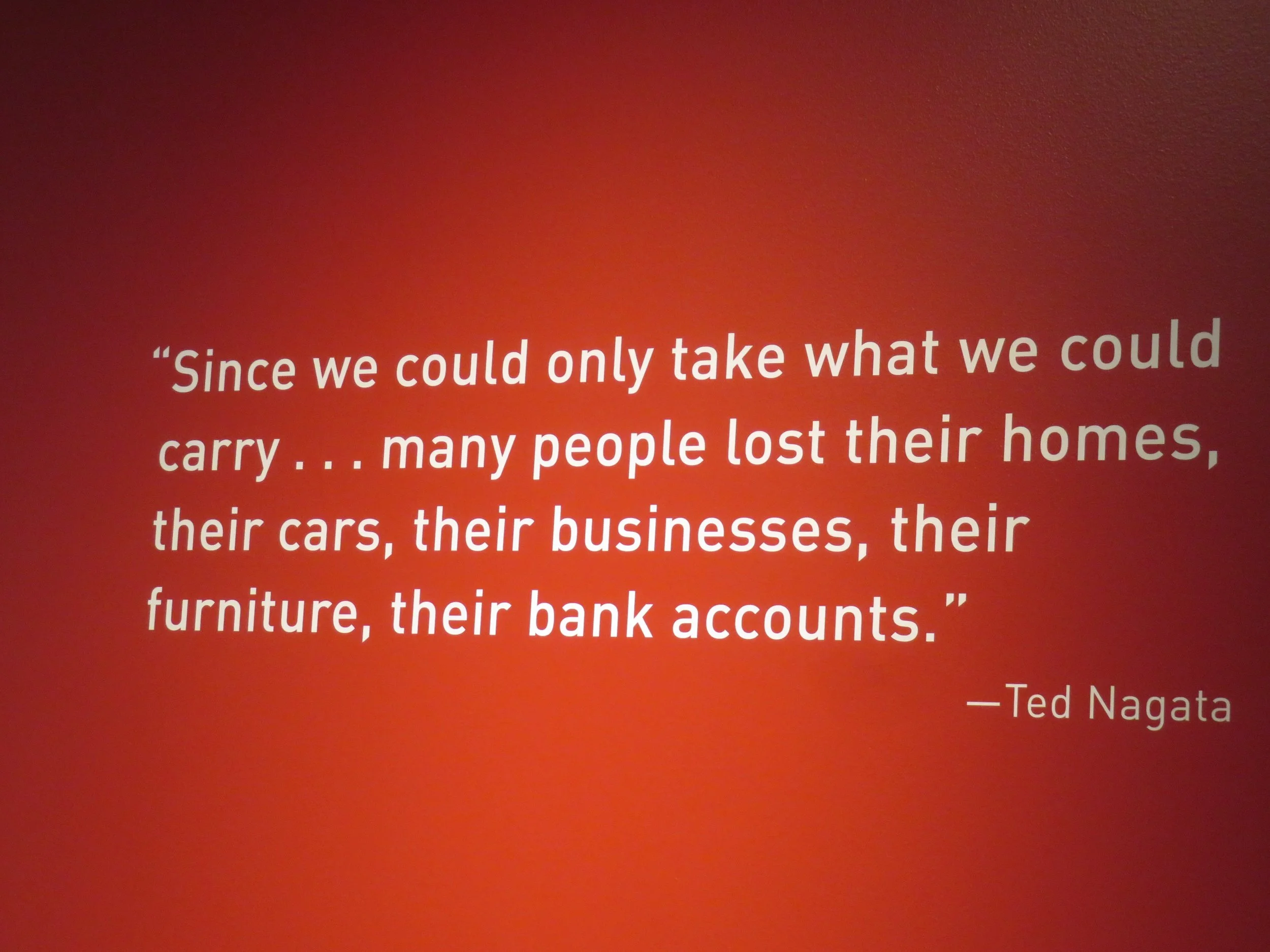

Ralph’s parents were given one week to sell their business, house and car, and could only take with them what they could carry. They were put on a train and sent to a temporary camp, set up in the stables of an abandoned horse racetrack while a more permanent camp was being built. Eventually they were moved to the Amache relocation camp in southeastern Colorado where they remained incarcerated for the duration of the war.

The JApanese Americans were forced to sell everything

Sadly, I’ve long since lost touch with Ralph, but I was reminded of the ordeal his parents endured when Marcie and I visited the Topaz Museum in Delta, Utah. Topaz is the name of the interment camp that was located about 15 miles northwest of Delta, and like Amache, it was used to incarcerate Japanese Americans during World War II. As Marcie said in her last blog, the museum is a gem, and does an excellent job of documenting the history and story of the camp and its incarcerees.

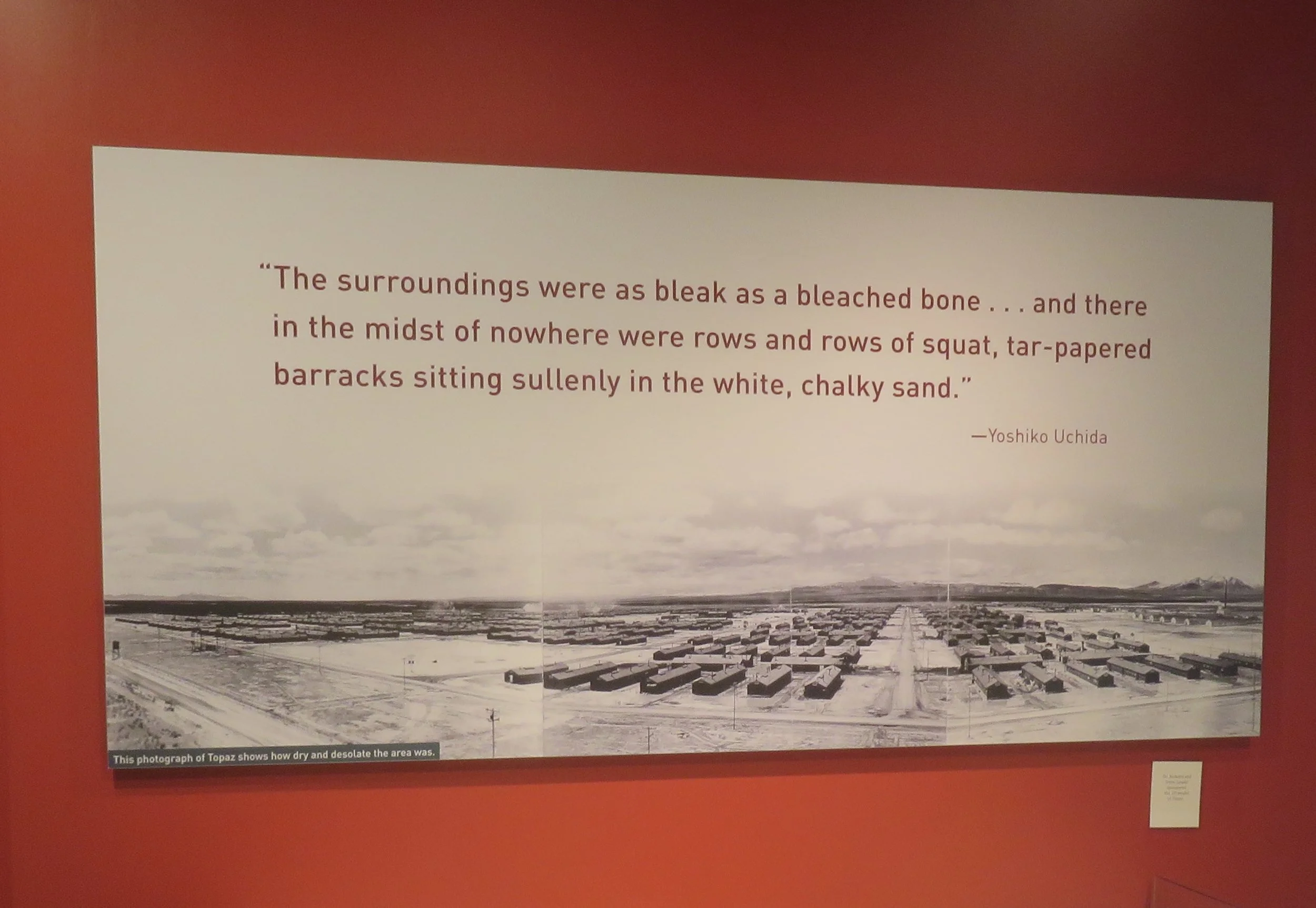

One of many very impressive displays at the Topaz Museum

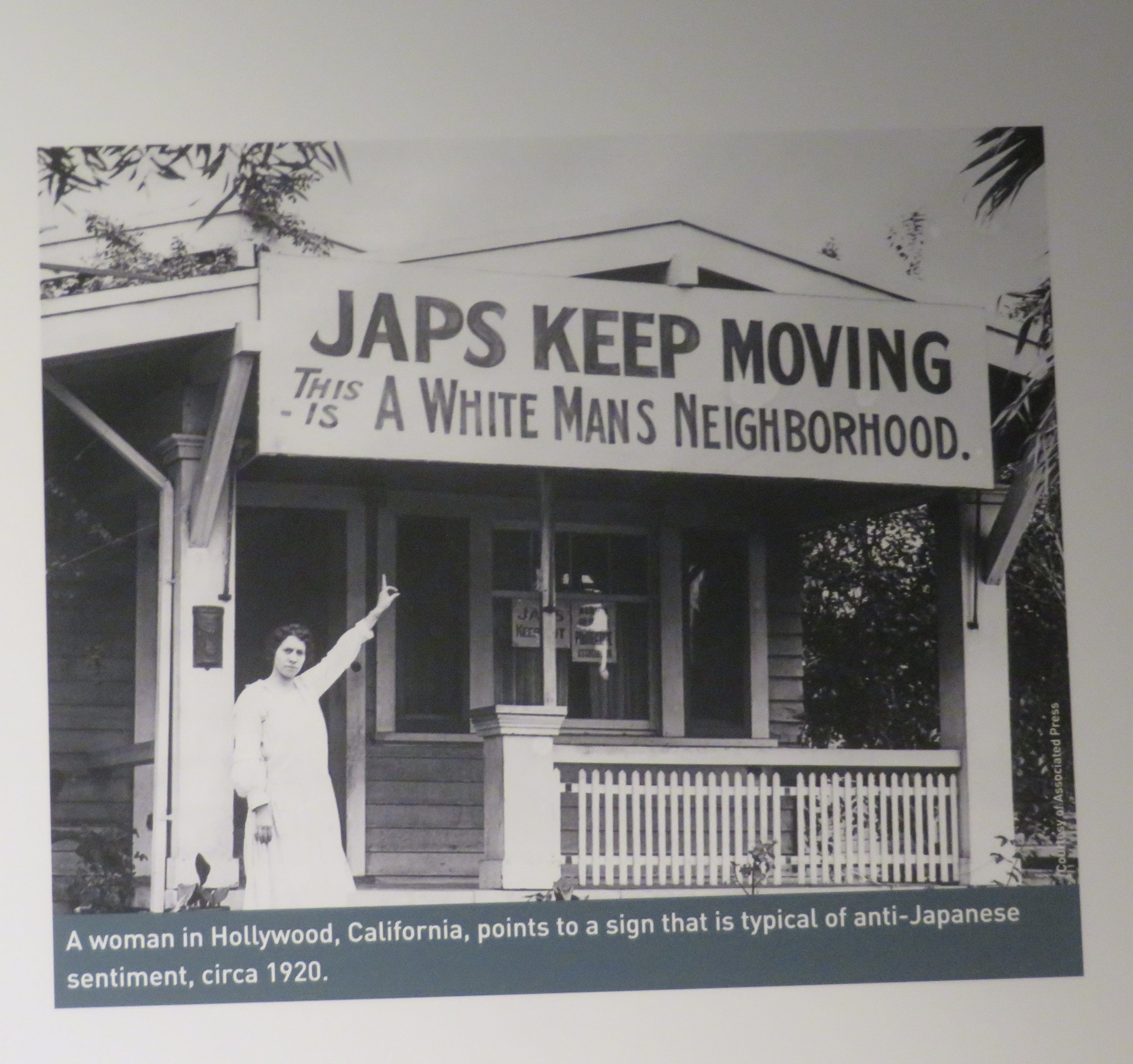

There was much anti-japanese sentiment during wwii

From the museum: “Topaz contained a living complex known as the "city", about 1 square mile (2.6 km2), as well as extensive agricultural lands. Within the city, 42 blocks were for internees, 34 of which were residential. Each residential block housed 200–300 people, housed in barracks that held five people within a single 20-by-20-foot (6.1 by 6.1 m) room. Families were generally housed together, while single adults would be housed with four other unrelated individuals. Residential blocks also contained a recreation hall, a mess hall, an office for the block manager, and a combined laundry/toilet/bathing facility. Each block contained only four bathtubs for all the women and four showers for all the men living there. These packed conditions often resulted in little privacy for residents.”

At any given time, there were about 9,000 internees living at Topaz, making it, at the time, the fifth largest city in Utah. The temperatures in this high desert climate dropped well below freezing in the winter. In fact, the average temperature in January was 26° F. Conditions were very uncomfortable, to say the least, in the uninsulated buildings they were given to live in, even after the belated installation of pot-bellied stoves.

What a typical room for a family of 4-6 looked like

The other seasons were also hard on the internees. During spring and fall, heavy rain turned the clay soil to mud, making it a difficult slog getting between buildings. During the summers, powerful winds and dust storms occurred frequently, coating everything with a heavy layer of dust. In 1944, one storm actually caused structural damage to 75 buildings.

Throughout the war, interned Japanese Americans protested against their treatment and insisted that they be recognized as loyal Americans. Many sought to demonstrate their patriotism by trying to enlist in the armed forces. Although early in the war Japanese Americans were barred from military service, by 1943 the army had begun actively recruiting men of Japanese descent (Nisei) to join the new, all-Japanese American unit, the 442nd Infantry Regiment. More than 12,000 Nisei men volunteered from the internment camps, of which nearly 4,200 were accepted. The regiment, including the 100th Infantry Battalion, fought in the European theater, and was the most decorated unit in U.S. military history. It also had one of the highest casualty rates. As several officers noted, the regiment was often used as canon fodder.

In one battle, 245 men of the 141st Regiment were cut off and surrounded by German forces. The 442nd Nisei Regiment was ordered to break through and rescue them. For the next few days, the 442nd engaged in some of the heaviest fighting of the war. They eventually broke through the German lines, rescuing the men of the 141st, but not without sustaining enormous losses. The 100th Battalion, part of the 442nd, saw casualties amounting to 73% of the unit’s men. Three weeks earlier, the unit had 2,943 men, but only 800 remained after the battle. More than 2,100 men were killed, wounded or missing to save the 245 men of the 141st Regiment.

On December 18, 1944, in Korematsu v. United States, the Supreme Court unanimously declared that loyal citizens of the United States, regardless of cultural descent, could not be detained without cause - thus paving the way for the release of the incarcerated Japanese Americans. The following day, the Roosevelt administration issued Public Proclamation No. 21, rescinding the exclusion orders and declaring that Japanese Americans would be released the next month. While they were allowed to leave the camps, they were not allowed to return to the West Coast until January 2, 1945, however. The released inmates were given $25 and a train ticket to wherever they wanted to go, but many had little or nothing to return to, having lost their homes and businesses.

It’s estimated that the internees lost more than $400 million in property during their incarceration. In 1948, Congress agreed to provide reparations for those that could document their losses. Due to the time pressure and strict limits on how much they could take to the camps, few were able to preserve detailed tax and financial records during the evacuation process. Therefore, it was extremely difficult for claimants to establish that their claims were valid. In the end, only $38 million was paid in reparations. Forty years later, an additional $20,000 was paid to those surviving individuals who had been detained in the camps. All told, this was far, far less than what they lost.

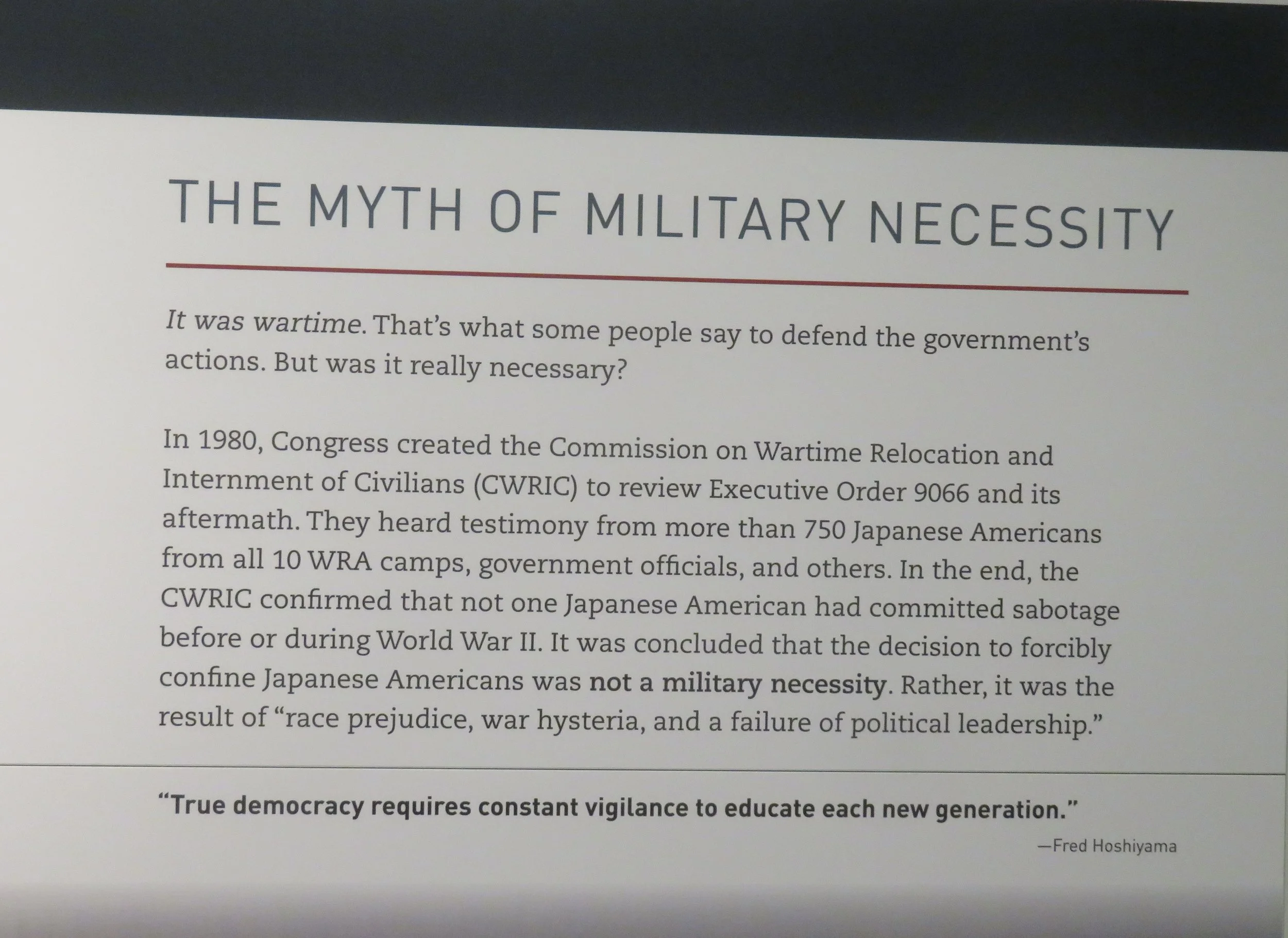

Ironically, while not a single person of Japanese ancestry living in the United States was ever convicted of any serious act of espionage or sabotage during World War II, 18 white individuals were tried for spying for Japan, of which 10 were convicted. The primary Japanese spy was a Japanese national based at the Japanese consulate in Hawaii.

Not one JAPANESE american committed an act of sabotage or espionage during wwii