The Fascinating Story of the Cape Cod Canal

/A view of the Cape Cod Canal

On our way to the eastern terminus of US-6 at Provincetown at the tip of Cape Cod, we drove alongside the Cape Cod Canal. The current caused by the ebbing tide was quite strong, making it appear as if the canal was actually a river flowing out to sea, but we knew from our experience when navigating the canal in Nine of Cups, that in a few hours the current would be flowing just as strongly in the opposite direction. Timing was everything - traversing the canal at the wrong time meant the best headway we could make was about 1 knot, while if we waited for the rising tide, we’d cruise along nicely at 10 knots.

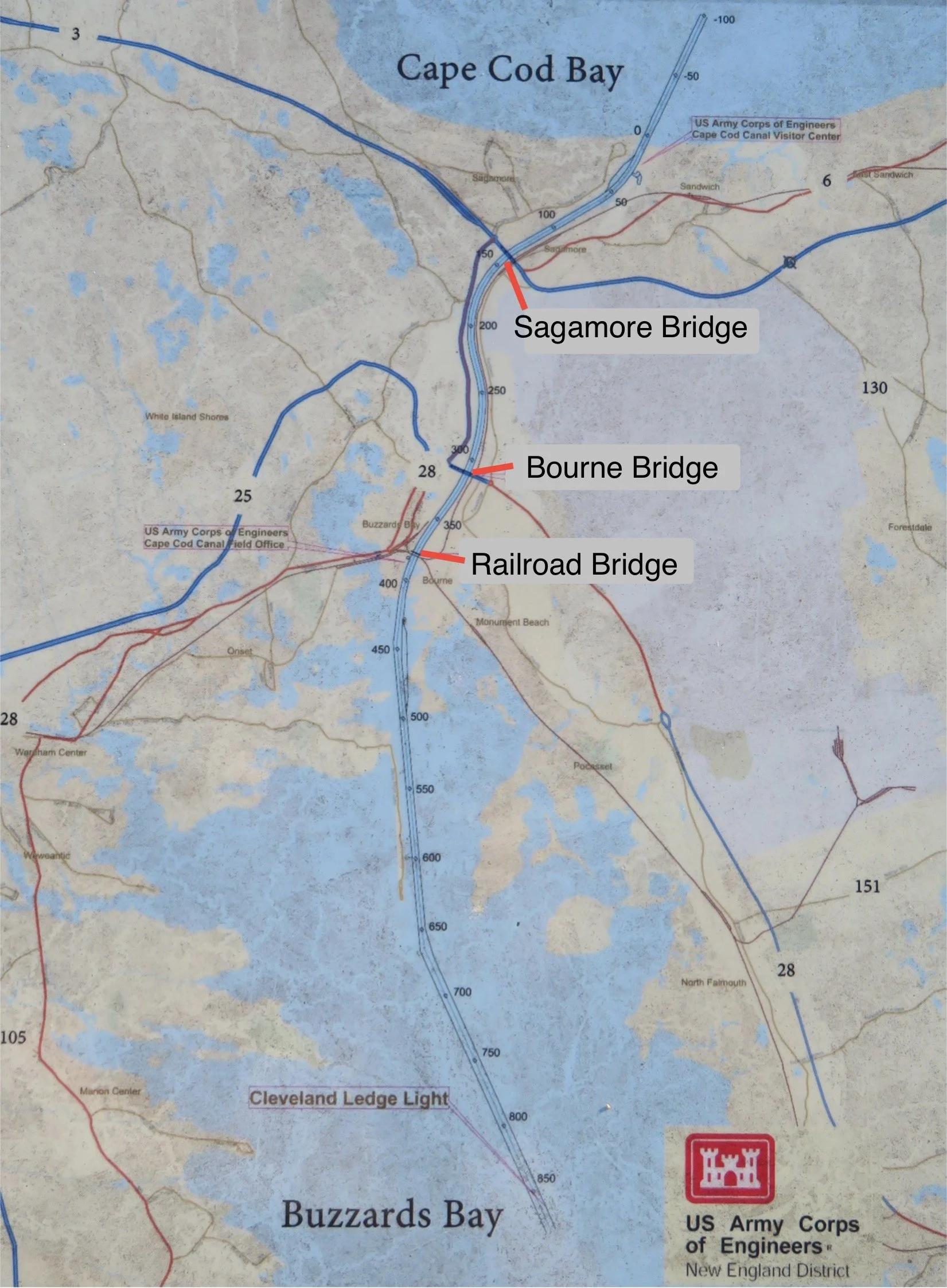

The Cape Cod Canal is a 17-mile waterway that connects Buzzards Bay to Cape Cod Bay allowing vessels to bypass the much longer route around Cape Cod - a route that can be quite treacherous for small vessels. It is considerably shorter and faster for ships traveling between New York and Boston.

The idea of building the canal was documented as early as the 1600s. The Pilgrims, who were located at Plymouth on Cape Cod Bay, had established a trading post with the Native Americans and the Dutch on the Mamomet River, which was located near Buzzards Bay. To reach this post, it was necessary to sail down the coast, along the Scusset River, and then traverse a three mile portage. In 1623, Miles Standish proposed digging a canal to create an all-water route, but it wasn’t until 1717 when a small ditch, named Jeremiah’s Gutter, was dug that allowed small, shallow draft boats to pass at high tide.

In 1776, General George Washington recognized that a canal would be of strategic importance by providing greater protection for the American fleet, and assigned the task of investigating its feasibility to an engineer named Thomas Machin. Machin completed the first known survey, and concluded that a ship canal without locks could be built, although the tidal currents would be quite strong. The cost was, however, beyond what the fledgling Continental Congress was willing to spend.

Over the following 125 years, a number of other surveys were completed and a few attempts were made to build a canal. None had the engineering or financial resources necessary to complete the project, and all ended in failure. The need for a canal was quite evident - during this same period, the dangerous outer banks of Cape Cod became known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic”. In the 1880s, shipwrecks occurred at a frequency of once every two weeks, and according to the Cape Cod National Seashore, there are over 1,000 shipwrecks off the coast of Cape Cod.

Shipping routes through the canal

In 1904, financier August Belmont II teamed up with a renowned civil engineer named William Parsons to, once again, attempt building the canal. After several surveys and studies were completed, and once adequate funding was pledged, construction began in 1909. Almost immediately, numerous complications developed. One complication was the discovery of huge glacial boulders that were unable to be moved by the available men or machinery. Newly invented steam shovels were purchased, and a dedicated railroad line was built to carry the debris away. All these complications caused the project to run way over budget and well behind schedule, but it was finally completed on July 29, 1914, when it began operation as a private toll waterway.

Unfortunately, the channel was narrow, only 100 feet wide in places, and that coupled with the swift tidal currents caused frequent accidents. As a result, mariners avoided it and the canal never achieved the level of traffic needed to make it a financial success. In 1927, Belmont and his investors sold it to the federal government for $11.7 million.

Over the next decade, the Army Corp of Engineers undertook a major upgrade to the canal. One major problem with the canal was the opening bridges - many of the shipping accidents were due to vessels having to remain in place, fighting the heavy currents, while waiting for a bridge to open. The Corp replaced the opening bridges with two fixed bridges for cars, the Bourne and the Sagamore, and one railroad bridge, each with a minimum height of 135’. They also widened the canal and dredged it to a minimum depth of 35’. These changes made the canal passable by even large ocean going ships.

Its strategic value was evident during WWII when ships sailing outside the cape were exposed to attacks by German submarines. Within the first seven months after war had been declared, five Allied ships were sunk by U-boats off the cape. For example, in 1942, a cargo ship, the SS Stephen R. Jones, ran aground and sank, completely blocking the canal, and forcing shipping to be rerouted around Cape Cod. As a result, on July 3, a U.S. Navy Liberty ship, the SS Alexander Macon, was torpedoed and sunk by a German sub, resulting in the loss of 10 lives. The German submarine, the U-215 was later depth-charged and sunk by a British anti-sub vessel. Shortly after, the canal was reopened when the Stephen R. Jones was removed - with the assistance of 17 tons of dynamite. (I thought this was a misprint - 17 tons is a lot of dynamite - but three separate sources confirmed it.)

Sister ship to the SS Alexander Macomb that was sunk by a German u-boat. courtesy of Wikipedia

Today, the canal and bridges are still operated and maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and smaller ships, fishing vessels and pleasure craft regularly utilize the canal. The railroad bridge is still used by freight trains and seasonal tourist trains. The traffic bridges, now 90 years old, are, however, reaching the end of their usable life and in poor condition and functionally obsolete. They were originally designed to handle 1 million cars a year, but now about 38 million cars a year pass over them -resulting in massive bottlenecks and delays, especially during the summer months. Replacing the two vehicle bridges will begin with the Sagamore Bridge beginning in 2027, with completion around 2034, followed by the Bourne. Total cost will be around $4.5 billion.

Whew - I’m so glad we made the trip now, during the winter when traffic was light. I can only imagine how eager Cape Cod residents must be looking forward to 14 years of construction!

BTW, if you ever get the chance to go whale watching in Cape Cod Bay, don’t pass it up. While sailing there on Nine of Cups, we had a most up-close and personal visit by a whale - one of the most memorable experiences of our 18 years aboard.

See you next week…