First Snow - A Tribute to Snowflake Bentley

/I'm not crazy about snow. We're sailors … not skiers nor snowboarders nor ski-mobilers. Snow is cold, wet and many times needs to be shoveled. It makes driving hazardous. All that said, there's something about the first snowfall of the year that's nostalgic and uniquely beautiful … like each snowflake itself.

I remember reading that the anthropologist, Franz Boa, postulated that Eskimos (translated into current PC, that's the many dialects of the Yupik and Inuit languages) had over 1,000 words for snow. That theory has certainly been contested over the years. I wonder if the Inuits have a word for “lazy” snow … because that's my favorite. Watching big, individual flakes float down lazily before your eyes is mesmerizing. It's a good time to go outside, stick out your tongue and let the snowflakes just melt there. It's magic. Once snow accumulates a bit, it weighs heavy on the tree boughs and muffles sound. A comforting, welcome silence settles over the shimmering, white neighborhood.

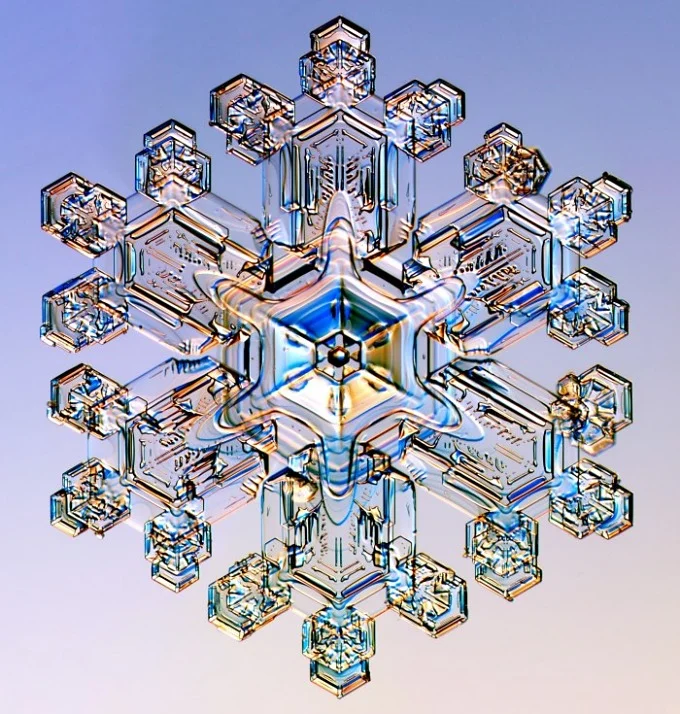

After visiting the tiny museum in Jericho, Vermont in early October, I've been thinking about Snowflake Bentley quite a bit. Snowflake Bentley, aka Wilson A. Bentley, native of Jericho, first proposed the theory that no two snowflakes were alike. He was enthralled with snow and frost. His photographs of snowflakes to document their unique crystal formations was a lifetime passion. Obviously done outside in icy cold weather, he pioneered in the field of photomicrography. I've never tried photographing snowflakes or frost. This year, I might.

I found a CalTech website on snowflakes that's incredibly informative and fun. You can learn something about snowflakes, find out why snow is white and/or download snowflake wallpaper.

Snowflake Bentley, by the way, is also a wonderful children's book about the snowflake man. Exquisitely illustrated, it's magic for adults, too. I might just get one for someone special this winter. It’s out of print, but available used on several used book seller sites.

A self educated farmer, Bentley attracted world attention with his pioneering work in the area of photomicrography, most notably his extensive work with snow crystals (commonly known as snowflakes). By adapting a microscope to a bellows camera, and years of trial and error, he became the first person to photograph a single snow crystal in 1885.

He would go on to capture more than 5000 snowflakes during his lifetime, not finding any two alike. His snow crystal photomicrographs were acquired by colleges and universities throughout the world and he published many articles for magazines and journals including, Scientific American and National Geographic.