The Blue View - The Cape Effect

/Wind behaves much like a fluid. As it encounters a mass of land, it speeds up as it goes over or around the obstacle, much like the water in a river does as it goes through a narrows or around a boulder. This phenomenon is very apparent on a sailboat as the boat nears the end of an island or a cape. We have often been sailing in very light winds in the lee of an island, only to get blasted by 35 knots or more of wind as we cleared the end of it. Likewise, as Nine of Cups nears a cape or headland from offshore in moderate 20-30 knot winds, we know that the wind will be considerably higher just before we go into the lee of the land.

This phenomenon is often referred to as the cape effect. Most capes mark the end of a landmass, many of which are high promontories or even mountains. When the wind conditions are right, these capes can be dangerous. Usually, giving the cape a wide berth will avoid the worst of the wind. Depending on the cape and the current weather conditions, this might mean staying a mile or even five miles offshore.

Regional weather patterns as well as the local topography can greatly enhance the cape effect. As anyone who has sailed the eastern Caribbean can attest to, the mountainous islands coupled with the strong tradewinds prevalent there often make for boisterous sailing between islands. Likewise, “Windy Wellington” is situated in the Cook Strait, the small gap between the north and south islands of New Zealand. The wind, which is funneled between the two land masses, blew hard every minute of the week or so we spent there.

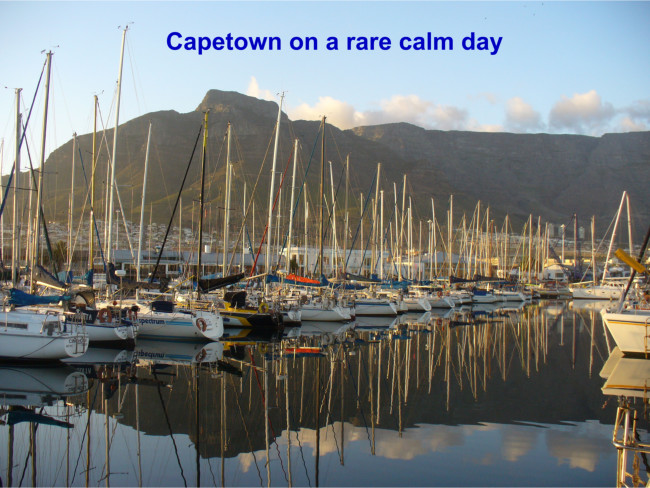

When we think of Capetown, which is nestled at the foot of Table Mountain, what we remember most about the city, beyond its sheer beauty, is the wind. The combination of the height of the mountain, the frequent inversion layers that prevent the wind from going over the top of the mountain and the local weather patterns result in almost consistently strong winds in Capetown, and at Cape Point a few miles south. It is not unusual to have gale force winds in Capetown and Cape Point, while totally calm conditions exist in Clifton, halfway in between.

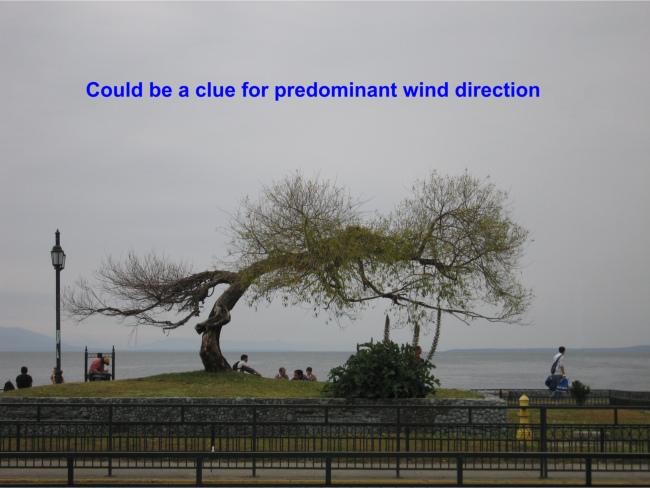

There are other topographies that have this effect as well. A gap between two mountains or a notch in a mountain will often funnel and magnify the wind. While this isn't called a cape effect, the result is the same – the wind speed increases as it is redirected through the notch or gap. This effect may not be too noticeable in light winds, but when we are taking shelter from an impending gale or storm, we try to avoid anchoring in such places. As we approach an anchorage, we pay as much attention to the hills and valleys we will be anchoring behind as we do to the depth sounder, water color and charts. Other clues are trees that are bent from the wind or gaps in the trees below a notch or between two hills.

And there is one other clue as well. If the bay is named Windy Bay, Storm Bay, or Seasick Cove, it might be a good idea to look into how the anchorage got its name. It probably wasn't named after Bill Windy or Mary Storm.