Communications Aboard

/Tony follows our blog regularly and comments often, asking relevant questions as he prepares himself and his boat to head off sailing into the sunset one day. Recently, after reading our post on Social Media for Cruisers, he asked about communications aboard. We thought we'd offer this article we wrote awhile back for Ocean Navigator as an overview of the types of communications we have aboard Nine of Cups. In the 15 years since we have been cruising, we have seen some vastly significant improvements in communications … both at sea and in port. Truth be told, we're usually way behind the times. We still do not use a SAT phone, primarily because the technology is still slow and monthly costs incurred are too painful for our budget. While costs are coming down and the technology continues to advance, cruising friends have reported that it still costs them between $500-$1000 per year for limited e-mail and weather forecasts.

We still rely on our trusty ICOM single-side band (SSB) radio in conjunction with SailMail ($250/yr) for e-mails at sea and downloading GRIB and other weather files. The SailMail “shadow mail” function allows us to monitor our incoming Yahoo land e-mails and selectively download them. It's slow, but affordable and mostly reliable. We also use our SSB for participating in cruiser nets during passages, something we would not be able to do with a SAT phone. That said, however, and despite budget constraints, if we were to start all over again, we might consider the Iridium Go! or some comparable SAT phone system rather than invest in SSB.

Though it's necessary to have aboard, we seem to use our VHF less and less. Interestingly, outside of the USA, we've found that many marinas do not use VHF communication at all. They expect an e-mail or a call prior to arrival which is a challenge when we're just arriving in a new country and have no mobile phone available. VHF at sea is used exclusively for emergency and ship-to-ship contact. Once in port, VHF use is totally dependent on the area. In Opua, New Zealand, for instance, there was a local, daily net on VHF and cruisers contacted each other on VHF constantly, making the radio traffic quite bothersome at times. In other ports, VHF is used for contacting authorities (Port Authority or Coast Guard) for arriving or reporting boat movement, but we rarely hear a cruiser hail. Instead, mobile (cell) phone communication is the norm between cruisers nowadays. Our Standard Horizons VHF also provides us with passive AIS and DSC communications … a whole other blog topic.

We originally had two-way radios to communicate with each other when we went ashore. We gave those up years ago and instead invested in a couple of unlocked, generic mobile phones. The purchase of inexpensive SIM cards on arrival in a new country is usually one of our first orders of business after clearing in. The process of setting up service in the new country, however, is sometimes convoluted and time-consuming and the documentation requirements vary. We usually choose a pay-as-you-go plan which allows us to buy more time via the internet or at local shops. We tend to text each other, rather than calling because it is more economical.

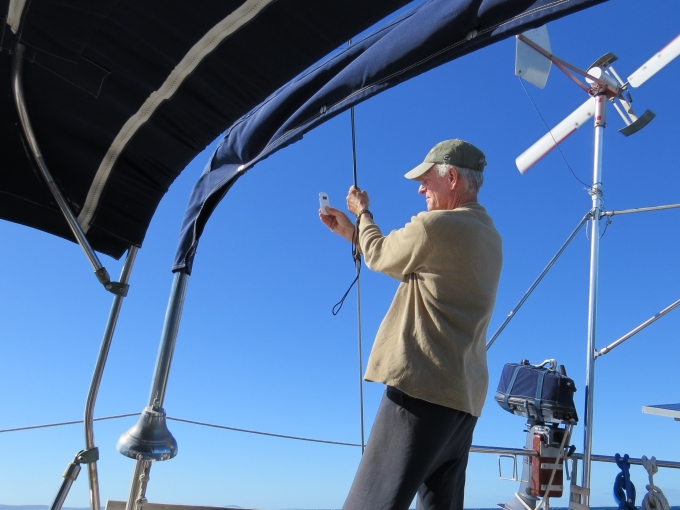

We've also purchased internet dongles when available which affords us the luxury of having internet aboard. Frequently, there are introductory offers which include the dongle purchase as well as a certain amount of data bytes at a bargain price. This worked especially well in many parts of the South Pacific and Australia when we had internet on-board all the time while in port or at anchor, and up to 10 miles offshore for most of our coastal passages. Sometimes it took some acrobatics to obtain a good signal, reminiscent of adjusting the rabbit ears on old TV sets. We usually have to pay for data by the kilobyte, thus we rarely do video streaming, large downloads or random internet surfing because of the cost.

In our early days of cruising, we found internet kiosks ashore and used their house-computers for e-mails, but we were always justifiably paranoid when we wanted to do any banking transactions or parts purchasing which required us to input our credit card numbers. We rarely need to use internet kiosks any longer.

Many marinas worldwide now offer free internet, but the signals never seem to be all that strong. We graduated to an antenna aboard in 2007 which was reliable within ½ mile. It had its limitations, but it was a step-up from using the kiosks, for sure. When internet was not available in an area, we lugged the laptop to a free hotspot ashore each day (or several times a day) to connect to the internet. We recently upgraded to a high-powered wifi antenna and receiver along with a mini-router which we now rely upon heavily for the convenience of internet on the boat. Its maximum range is reportedly seven miles and we reliably pick up signals at least a couple of miles away. If we're not in a marina with free wifi or we don't have a prepaid internet subscription, it is rare that we find an unsecured, free wifi hotspot from the boat. We don't mind paying for access if it's available. Otherwise, we carry our tablets to shore and find a local coffee shop or McDonald's for our internet hit of the day.

Calling home has changed dramatically over the years as well. We no longer have to find a phone booth (what's that?) or purchase phone cards for long distance calling. We have Skype apps for both the laptops and the tablets and have encouraged friends and family around the world to use Skype as well. Calls home are frequent and free.

One of the slowest forms of cruiser communication is the traditional “coconut telegraph” which is still alive and well. Word of mouth between cruisers seems to pass from one boat to another, one port to another, and one country to another with adaptations as bizarre and diverse as the cruisers who pass along the messages and stories. If accuracy and speed are not criteria, this is probably the cheapest way to go.