The Blue View - Springing off a Dock

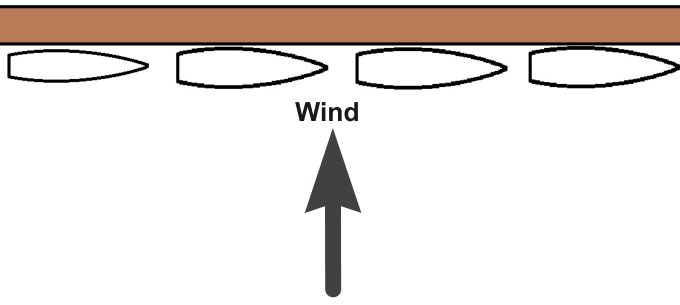

/When we are lying alongside a dock and there are boats tied up just in front of and behind us, departing can be a bit tricky. Add a contrary wind blowing us onto the dock and attempting to leave can be a real challenge. If the wind isn't blowing too hard, using a spring line will usually enable us to extract ourselves without damaging either Nine of Cups, the other vessels or our pride.

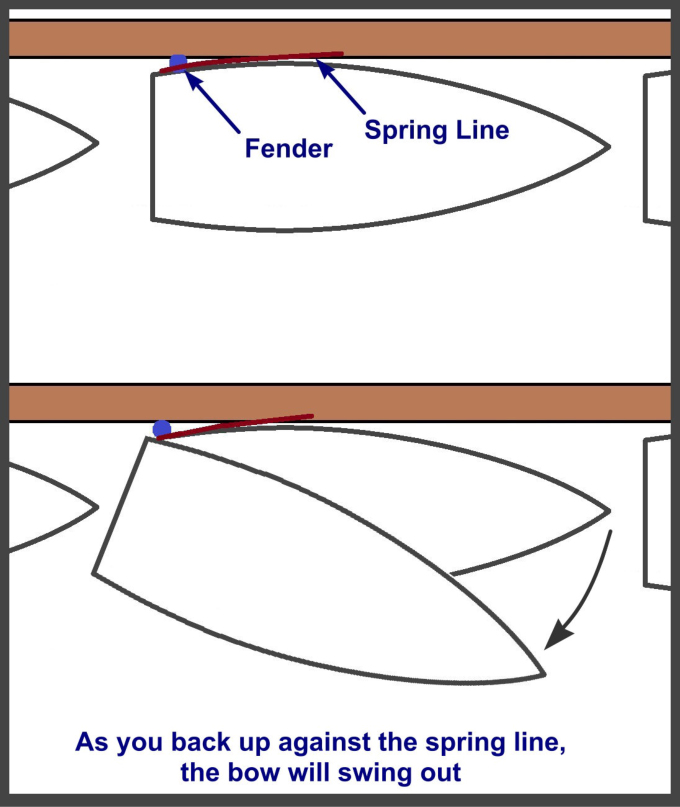

If the wind is very light, we use a stern spring line. We tie a large bowline in the end of a dock line and drop it over a dock cleat located close to midships. The other end of the line is secured to Nine of Cups at a cleat near the stern. Next, we position a fender at or slightly forward of the stern cleat. Since the stern will be swinging close to the dock, it is important to make sure there isn't a piling or other obstruction that could damage whatever is on the rail like an outboard or a solar panel. Once all the other dock-lines are released, we begin slowly backing up. As the spring line tensions, the stern will begin to pivot on the fender and the bow will start to swing out. We keep the engine in reverse, increasing the engine speed as necessary until the bow swings out enough to clear the boat in front of us. Then I put the engine in neutral which immediately takes the tension off the spring line. If there is someone on the dock, they remove the bowline from the cleat and toss it to us. If not, Marcie is quite adept at giving the dock line a flip to remove it from the dock cleat. As she pulls the line in, I motor forward and away from the dock.

If there is a moderate wind blowing, it is better to use a bow spring line. The spring line is attached to the bow and the fender is rigged forward. As Cups motors forward, tensioning the spring line, the stern will swing out. Once it is far enough out, I put Cups in neutral, taking the tension off the spring line, and it is removed from the dock cleat. I put the boat in reverse, and as we back away from the dock, the wind will blow the bow downwind. This is not the time to dawdle – I use a lot of throttle as we back away from the dock to make sure the wind doesn't blow Cups into our neighbor. I continue backing up until I find a spot with enough maneuvering room to turn around.

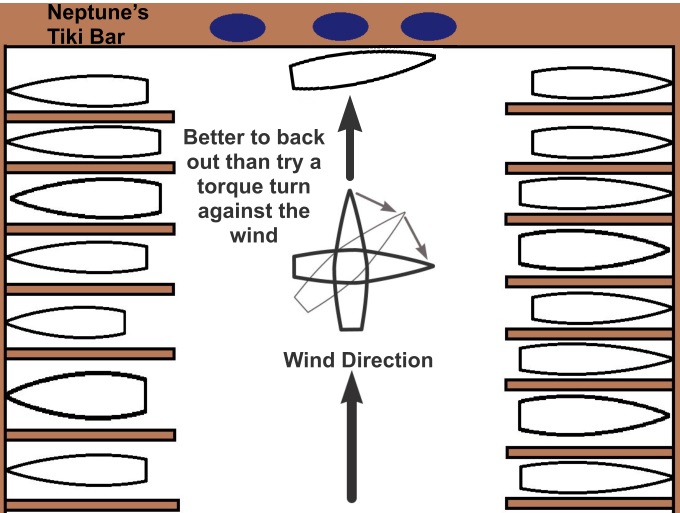

In my last Blue View, we found ourselves moored between the tables at a dockside tiki bar after botching a torque turn. We tried to extricate ourselves by springing off the dock, but that's when we learned that Nine of Cups has too much windage to manage it if the wind is stronger than 20 knots or so. An obliging sailor offered to take a bow line and secure it to a piling 100' (30m) upwind. Once he secured the line, we used the windlass to pull us off the dock. Once we were clear, he released the line, Marcie quickly pulled it aboard before it could get fouled in the prop (that would have really capped the evening), and we motored out of the marina.

I'm not sure whether the applause we received as we left was to congratulate us on finally getting off the dock or to thank us for providing the evening's entertainment. If the latter, we did not even consider going back for a curtain call.