The Blue View - Replacing a Halyard

/ One of the problems we had while crossing the Indian Ocean last year was a head sail halyard that parted. It starts at the deck, enters the mast about six feet up (2m) on the port side, exits the top of the mast and is attached to the head sail. We had last replaced it several years ago in New Zealand, and apparently it had been chafing against the main halyard all these years. Unfortunately, the spot that chafed was inside the mast at a location that never sees the light of day except on the rare occasion the head sail is removed, so we didn't see it coming and it eventually chafed through and parted. Fortunately, we were near the end of our passage and were able to furl the head sail and complete the passage with the staysail and reefed main.

One of the problems we had while crossing the Indian Ocean last year was a head sail halyard that parted. It starts at the deck, enters the mast about six feet up (2m) on the port side, exits the top of the mast and is attached to the head sail. We had last replaced it several years ago in New Zealand, and apparently it had been chafing against the main halyard all these years. Unfortunately, the spot that chafed was inside the mast at a location that never sees the light of day except on the rare occasion the head sail is removed, so we didn't see it coming and it eventually chafed through and parted. Fortunately, we were near the end of our passage and were able to furl the head sail and complete the passage with the staysail and reefed main.

Usually when we replace a halyard, we can use the old halyard as a messenger. We attach the end of the new halyard to the end of the old one, and as the old halyard is pulled out, the new one follows (See the Blue View – Reeving a New Halyard). In this case, however, the old one had parted and pulled out of the top of the mast. We wouldn't have wanted to use the old halyard as a messenger anyway, because if we routed the new halyard along the same path as the old, it too would chafe through in a few years. Better to route a new messenger.

Both the entry and exit points for the halyard were close to the port side, so we wanted the new halyard to lie close to the mast on the port side. If we simply dropped the new messenger down into the mast, it quite likely would foul one of the other halyards inside the mast. To avoid this, we put Nine of Cups on a heel to port. We attached a long line from the spinnaker halyard to a stout cleat on the end of a slip a few boat lengths away and using a cockpit winch, we tensioned the spinnaker halyard until Cups had a definite list to port. Had we been at anchor, we would have swung the boom out to the port side and hoisted the dinghy and engine from the end of it. Together, they weigh about 200 lbs – if this wasn't enough weight, we would have partially filled it with water.

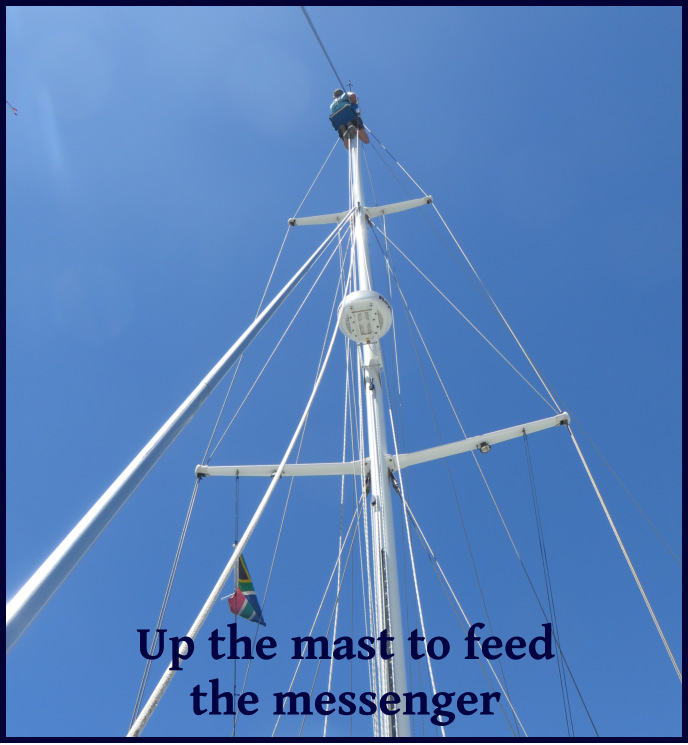

We removed the stainless trim piece from the entry hole for the halyard in the side of the mast, then I rigged up a messenger using 1/8” (3mm) line and a few fishing weights. I attached the opposite end of the messenger to the new halyard, then went up the mast. I lowered the messenger over the masthead block and down into the mast.

Marcie positioned herself at the halyard exit point and watched for the end of the messenger to appear. Using a bent wire, she fished the weights on the end of the messenger out of the mast. Then it was a simple matter to pull the remaining messenger and the attached halyard out of the bottom exit point on the mast as I fed the line from the top.

All that was left to do was reattach the trim piece and whip the halyard ends.