The Blue View - The Ditch vs Offshore

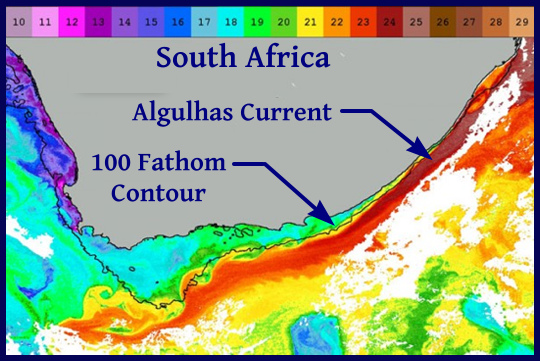

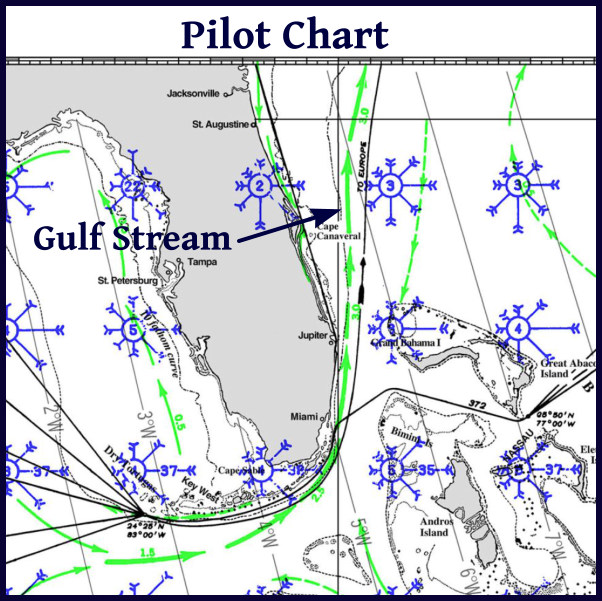

/Every year there is a migration of yachties from the south to north along the U.S. Atlantic coast in the spring, and then a reverse migration in the fall. They want to get north before hurricane season starts on June 1, and then want to get south before it gets too cold at the end of the hurricane season in December. I'm guessing, but there must be thousands of boats that join this migration each year. One way of making the trek is the offshore route. When going north, a boat can use the Gulf Stream to make a quick passage. Going back south, the Gulf Stream can be avoided by keeping close to shore, well within the 100 fathom depth contour, or by heading well offshore. This path often includes a stop at Bermuda, and is a good route if the destination is the Caribbean.

The other method is to follow the Intracoastal Waterway or ICW - often referred to as the Ditch. The ICW is a series of rivers, canals, inlets and lakes that are all interconnected. A boat can travel from New Jersey to Miami and beyond, all within protected inland waters and never enter the ocean.

There are a lot of positives to using the ICW, especially if the joy is in the journey. The pace is slow, and there are new and wonderful things to see at every bend, from urban seaports to dense swamps to bucolic villages to rolling hills and pastures. We know several cruisers who sail up and down the ICW every year and never tire of the diversity of things to see along the way.

We sailed portions of the ICW during our first two years of cruising, and we found that, for us, there were several pros and cons. The pros:

- Weather. Good, accurate weather reports are always available, and while encountering a thunderstorm in the confines of a narrow channel or river is no fun, usually there is some warning and a place to hunker down and wait it out. Likewise, if the weather calls for a day or two of crappy weather, we can find a protected anchorage and wait for it to pass. Offshore, we do the best planning we can, but once out there, we have to take what we get.

- Daylight travel. It's nice to be able to stop at the end of each day, drop the hook in a quiet anchorage, and enjoy dinner together, then maybe a movie before going to bed – as opposed to the three hours on/ three hours off of our night watch schedule while on a passage.

- Repairs. If something breaks on the ICW, it is almost always possible to stop and anchor long enough to make the repair, and help, if needed, is never too far away. Repairing things at sea is always more of a challenge, especially if the boat is rolling and pitching. I've often wished for a couple more hands and a prehensile tail so that I could keep myself, my tools and the parts I'm replacing from sliding around, banging into things and/or falling into the bilge or overboard.

- Internet. I never thought I'd say this, but we do miss our internet connection while at sea. Most of the ICW has at least cellular coverage, and wifi hotspots are common.

The cons:

- Motoring. We motored most of the sections we traveled, sailing very little and using a lot of fuel.

- Depths. The controlling depths are 10 feet between Norfolk, VA and Fort Pierce, FL, but what dredging is done doesn't keep up with the shoaling that occurs. We draw 7' 2”, which is quite deep for the ICW, and we found ourselves stuck in the mud on several occasions. I had read that if you stay in the marked channel, there will be plenty of water, but I vividly remember being hard aground while being smack-dab in the middle between a red and a green channel marker. I've yet talked to a cruiser that draws more than 6 feet that didn't run aground at least once while traveling any distance on the ICW. Some of the new apps, like Active Captain help in this regard. They compile comments and notes from hundreds of other cruisers who have navigated the same waters ahead of you, providing a wealth of current local information about hazards and shoaling.

- Hand Steering. We are used to sailing long, offshore passages, where the autopilot does most of the steering. We still keep watch, but it usually doesn't require the same constant vigilance as hand steering along a narrow channel.

- Low Daily Distances. The pace is slow and, for the most part, traveling along the ICW is only during daylight hours. We averaged 50-60 miles a day, and typically stayed put every third or fourth day. This can a positive – who doesn't dream about taking a slow, leisurely trip along most of the eastern seaboard. On the other hand, we usually dawdle too long in whatever place we are, and end up having to rush to make up time.

- Stress. There certainly are stressful moments on an offshore passage, but if the weather is good and nothing major breaks, ocean passages are usually pretty benign. The ICW can be stressful, especially at first, from unexpected shoals, narrow bridges, cross currents, thunderstorms, tugs and barges that need almost the entire channel, power boats passing at high speed, other yachties, and the constant vigilance that is required just to keep us in the channel. I was exhausted at the end of each day until I started getting into the groove.

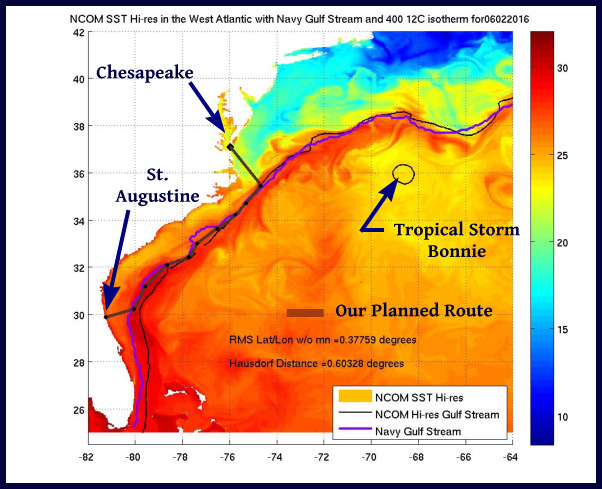

So what will we do? As usual, we stayed too long in Trinidad, Puerto Rico, and now St. Augustine, and we will have to make a beeline for the Chesapeake. Next fall, however, we may do a good portion of the ICW on our way south – assuming we can extricate ourselves from the charms of the Chesapeake.

We are very conservative sailors. We reef down before we need to when we see potentially bad weather approaching or in the evenings when we can't always see a squall coming our way until it is on top of us. Likewise, we use less sail than we did a few years ago - we'd rather trade a few miles of distance each day for a more comfortable ride. We call it 'leisurely sailing' (although in our younger years we undoubtedly called it 'old fart sailing'). A good day for us now is 150 nautical miles, just over an average of six knots.

We are very conservative sailors. We reef down before we need to when we see potentially bad weather approaching or in the evenings when we can't always see a squall coming our way until it is on top of us. Likewise, we use less sail than we did a few years ago - we'd rather trade a few miles of distance each day for a more comfortable ride. We call it 'leisurely sailing' (although in our younger years we undoubtedly called it 'old fart sailing'). A good day for us now is 150 nautical miles, just over an average of six knots.

We've had a taste of three tropical storms during our sailing days – one in a marina and two at sea. When we were still chartering boats a few decades ago, we learned that the rates were significantly less if we rented a boat during hurricane season. I figured the odds of encountering a hurricane during the 10 days of each season we were chartering were pretty low. The odds caught up with us one year, however, when we took a direct hit from Hurricane Bertha in the British Virgin Islands. We hunkered down in a marina in Virgin Gorda, prepped and secured the boat as best we could, then sat through it. We watched coconuts fly through the air as though fired from a cannon, and had a brief “eye-of-the-storm” party before the second half of the storm assaulted us. It was only a Category 1 hurricane, and was more of an adventure than anything life threatening – especially since it was a chartered boat and not ours.

We've had a taste of three tropical storms during our sailing days – one in a marina and two at sea. When we were still chartering boats a few decades ago, we learned that the rates were significantly less if we rented a boat during hurricane season. I figured the odds of encountering a hurricane during the 10 days of each season we were chartering were pretty low. The odds caught up with us one year, however, when we took a direct hit from Hurricane Bertha in the British Virgin Islands. We hunkered down in a marina in Virgin Gorda, prepped and secured the boat as best we could, then sat through it. We watched coconuts fly through the air as though fired from a cannon, and had a brief “eye-of-the-storm” party before the second half of the storm assaulted us. It was only a Category 1 hurricane, and was more of an adventure than anything life threatening – especially since it was a chartered boat and not ours.

We'd just as soon not have any more encounters with tropical storms, hurricanes or cyclones, especially at sea, and now, as we are heading north up the east coast of the U.S., we're paying close attention to what's brewing out there. Hurricane season didn't officially start until June 1, but Tropical Storm Bonnie beat the gun, hitting the Carolinas on May 29

We'd just as soon not have any more encounters with tropical storms, hurricanes or cyclones, especially at sea, and now, as we are heading north up the east coast of the U.S., we're paying close attention to what's brewing out there. Hurricane season didn't officially start until June 1, but Tropical Storm Bonnie beat the gun, hitting the Carolinas on May 29