The Blue View - Fuses and Circuit Breakers

/Sooner or later, if you own your boat any length of time, you will have to deal with replacing or adding a DC electrical circuit. Perhaps you are upgrading an older piece of gear and the wiring is corroded or inadequate, maybe you are adding some new electronics, or maybe you are replacing a previous owner's amateurish handiwork that is now causing problems. Whatever the reason, it is not difficult to do the job correctly, with results that are professional looking, safe and reliable.

Planning the installation

Planning the installation

If you are upgrading an older piece of electrical gear, you may only need to replace the old wiring with new. If the amperage requirements of the new gear is no more than the old, if it was wired correctly to begin with, and the circuit it is connected to is not overloaded, it should be fine. Otherwise, you will need to find a new circuit for your power connection. So how do you go about finding the best place to connect the new wiring?

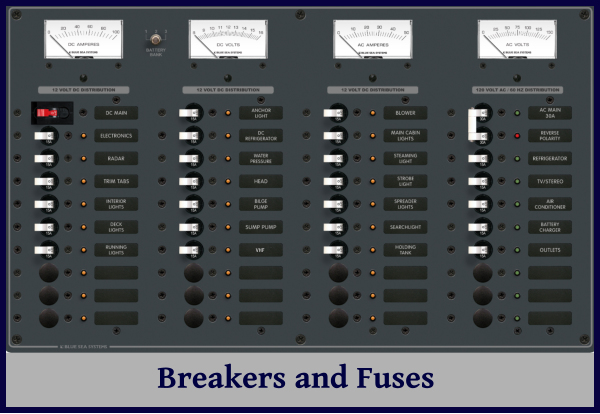

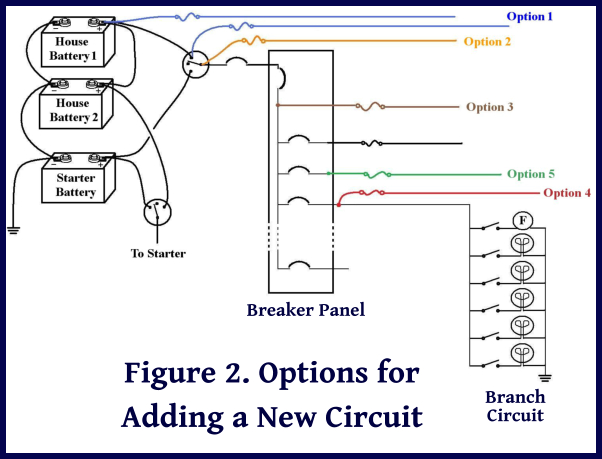

Figure 1 shows a simplified DC electrical schematic for a typical sailboat. It has two house batteries in parallel and one starter battery. The switches allow either battery bank to be disconnected or to be re-routed. For example, if the starter battery died, it is an easy matter to start the engine using the house battery bank. The breaker panel has one sub-main breaker and several branch breakers, only a few of which are shown in the figure.

Figure 2 shows several options for connecting your new electrical gear to the house batteries. Option 1, shown in blue, connects the new circuit directly to the battery. This is allowable for certain equipment that should be powered all the time, such as battery chargers, safety equipment (bilge pumps, alarms, etc.), and electronic equipment requiring continuous power for its memory. As long as there is a fuse or circuit breaker in the circuit and it is placed no more than 7” (178mm) from the battery or the switch, this method is acceptable. ( Note: if the conductor is enclosed in a sheath or enclosure, the fuse can be located up to 72” (182cm) from the battery terminal or within 40” (102cm) of the switch.)

The second option is to connect the new circuit to the battery switch as shown in orange in Figure 2. This is acceptable, again, as long as the fuse is within 7” (178mm) of the switch, or within 40” (101cm) of the switch if the conductor is contained in a sheath or enclosure. This option is better than the first for most equipment because the circuit can be switched off using the battery switch.

In the third option, the brown wiring in Figure 2, the new circuit is connected downstream of a circuit breaker. Depending on the type of equipment being connected and the conductor size, a fuse may or may not be required.

You can also connect the new circuit to an existing branch circuit as shown in red in Figure 2, which in some cases, may be the best option. As in the third option, a fuse may or may not be necessary depending on what you are installing. If you are adding a new reading light to the starboard settee, it makes perfect sense to connect it to the “Stb Cabin Lights” breaker. On the other hand, it would be illogical to connect the wiring for a new chart plotter to that same branch circuit. Before deciding on this fourth option, you should calculate the existing load on the branch circuit and make sure the new equipment will not overload the circuit. If the existing load plus the amperage requirements of the new circuit are less than the breaker size, it is probably safe to add the new circuit. In some cases, it might be possible to increase the breaker size, but this is unwise without carefully evaluating the conductor sizes and loads in an existing branch circuit. (The last few blogs discussed the processes for calculating loads and wire sizes).

One other option for connecting the new circuit is the green wiring shown in Figure 2. If you have a spare breaker, the circuit can be wired as a new branch circuit. This would be the best option if you are installing some new gear like an autopilot, refrigeration unit, or radar. The fuse may not be necessary if the breaker is sized correctly.

The two key things to remember are:

- Don't overload the circuit. If you are installing new gear, make sure the added load combined with the existing load doesn't draw more than the circuit can handle.

- Don't make the wire the weak link in the circuit. Be sure the wire you are adding to a circuit can carry the maximum current the breaker is rated for. If you connect a 20 AWG wire to a circuit with a 20 amp breaker and the wire shorts out, the red-hot wire with its smoking insulation will become the circuit fuse before the breaker trips. A better way is to add a small fuse between the breaker and the small wire.

Want to know how to install a fuse? Stay tuned to next week's blog.

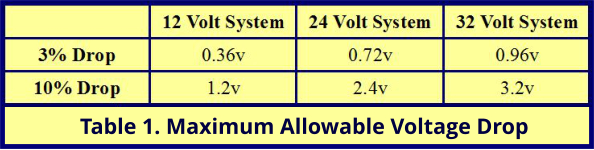

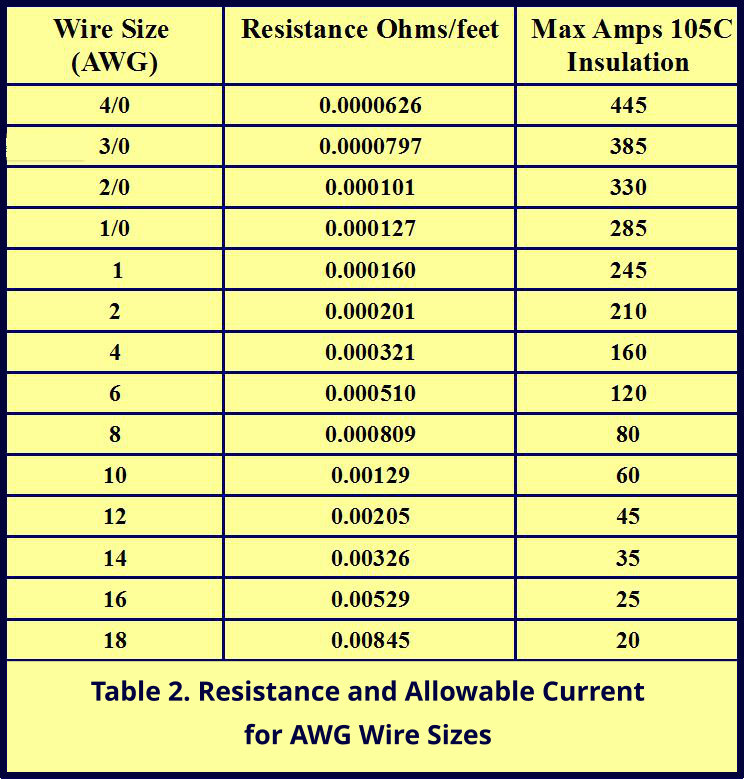

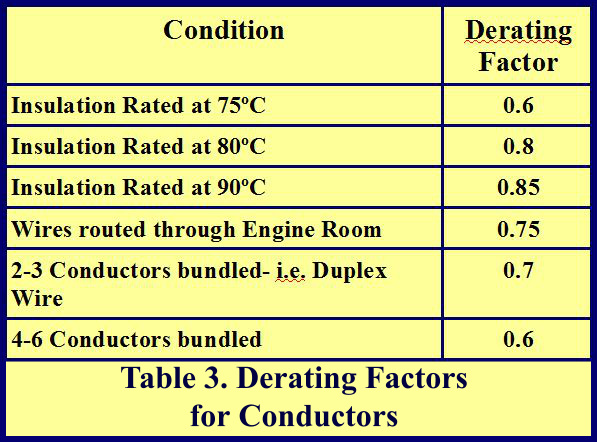

Last week's blog discussed one aspect of determining the correct wire size for an electrical application – how much current a wire can safely carry. Another aspect that should be considered is the amount of voltage drop that will occur.

Last week's blog discussed one aspect of determining the correct wire size for an electrical application – how much current a wire can safely carry. Another aspect that should be considered is the amount of voltage drop that will occur.