Blue View – Unsung Heroes... the WASP

/This isn’t a blog about those pesky little insects that build nests in inconvenient places, then get all upset and sting you if you encourage them to move on. Nope – this is about the Women Airforce Service Pilots or WASP. These were WWII women pilots who tested planes, ferried aircraft, and trained other pilots with the goal of freeing male pilots for combat roles. We’d never heard of the WASP until we visited the West of the Pecos Museum in Pecos, Texas which featured a tiny display devoted to these intrepid women flyers. The museum provided a brief overview of their story, and suggested visiting the WASP museum in Sweetwater, Texas.

As luck would have it, Sweetwater wasn’t that far out of our way on this trip, and we stopped in at the museum, part of Avenger Field on the outskirts of town, and spent a good hour or two learning about the WASP. And what an interesting visit it was…

We visited the WASP Museum in Sweetwater, TX

The Beginnings

WASP started out as two different organizations. Jackie Cochran proposed the idea of using women pilots in non-combat roles to Eleanor Roosevelt in 1939. Mrs. Roosevelt introduced Cochran to General Henry Arnold, head of the Army Air Force, who listened to her idea – then rejected it. To generate publicity for her proposal, she ferried a bomber to England, making her the first female to fly a military plane. While there, she, along with twenty-five other American women pilots she’d recruited, volunteered for the British Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) which had begun ferrying military aircraft for the English.

Not long after in early 1942, Col. William Tunner, head of the Ferrying Division of the Air Transport Command was having difficulty finding enough pilots to ferry, from factory to destination, the tens of thousands of aircraft being built. When he discovered that the wife of one of the men working for him, Nancy Harkness Love, was a very qualified female pilot, he met with her to find out if there were other capable female pilots. She convinced him that using experienced women pilots for ferrying duty was a workable idea, and he asked her to formulate a proposal. Within months, she had recruited twenty-eight pilots. “The Originals”, as they were known, formed the newly established Women’s Auxiliary Ferry Squadron”, or WAFS.

Meanwhile, Jackie Cochran got word of the formation of the WAFS, flew back from England, and confronted General Arnold. Cochran demanded that she be given the opportunity to form another unit of women pilots who would not only ferry aircraft, but tow gunnery targets, train combat troops on defending from strafing runs, and test newly repaired aircraft. Arnold granted her wish and formed the Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD) with Cochran as its head. In August of 1943, the two were merged to form the WASP, with Cochran as its head and Love in charge of the ferrying division.

Unlike the WAVES, WACS and SPARS, the WASP were employees of the Civil Service Commission. As civilians, the WASP had no insurance, no burial and death benefits, no military rank, and no veterans benefits.

Fifinella was a female gremlin designed by Walt Disney for a proposed film from Roald Dahl's book The Gremlins. During World War II, the WASP asked permission to use the image as their official mascot, and the Disney Company granted them the rights.

Fifinella, The WASP mascot created by walt Disney

Recruitment and Training

When the program was publicized, more than 25,000 women applied, but only 3000 already had a pilots license. Of these, 1830 women met all the criteria, passed the physical and were accepted. They were not part of the military, but, instead, were part of the Civil Service Commission. Because of this, they had to pay their own way to the training facility in Sweetwater and buy their own uniforms. They were paid $174.50 a month, but were charged room and board at the rate of $1.65/day.

Ground school included classes in meteorology, navigation, Morse code, parachute packing, mechanics, and 50 hours in the Link Trainer. Daily physical fitness was also part of the program. Those that passed the ground school moved on to flight training.

This guy’ll l never get past the Link Trainer

Flight training had three sections:

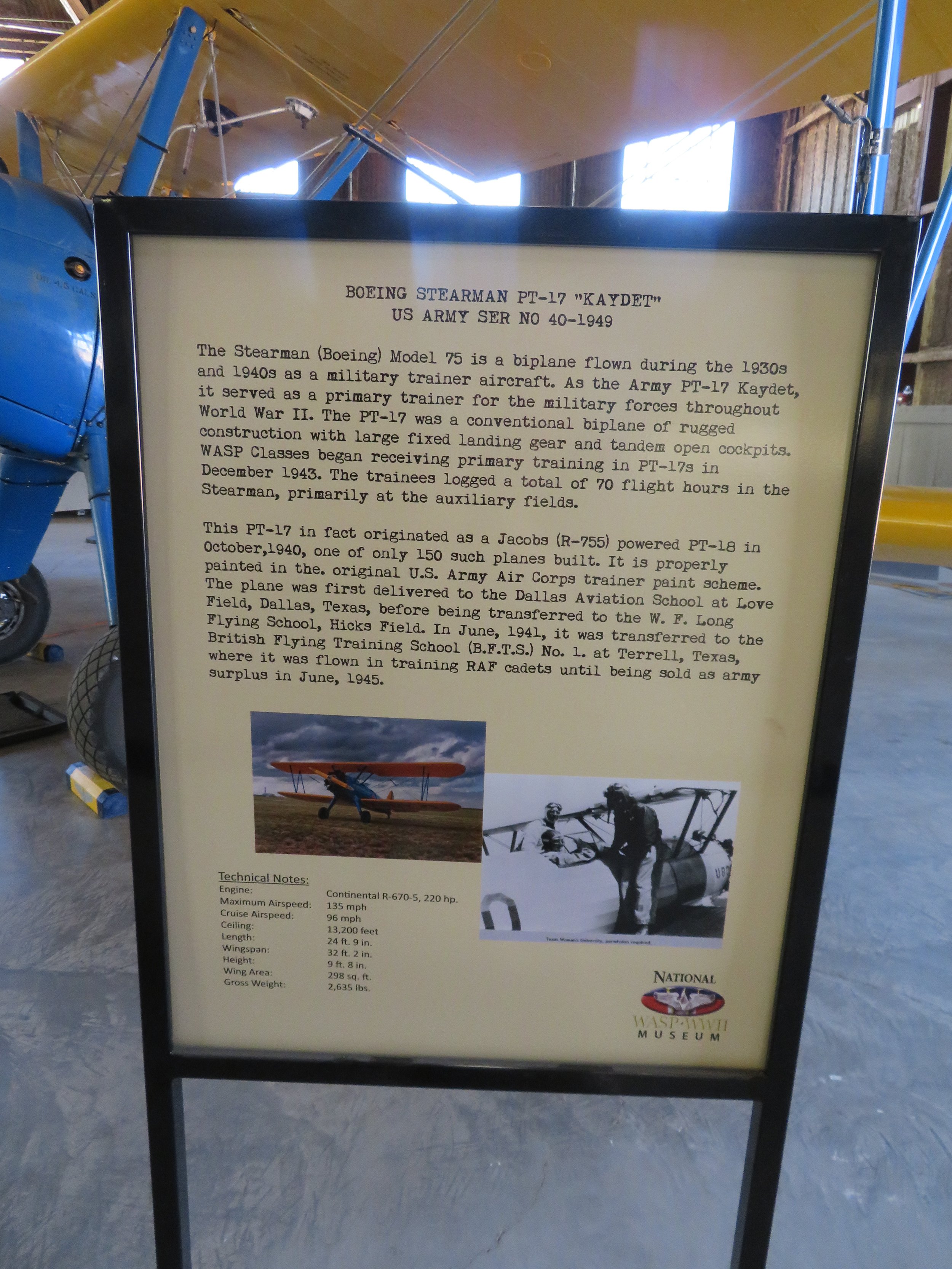

Primary Training – 70 hours flying PT-17s and PT-19s, light trainer craft.

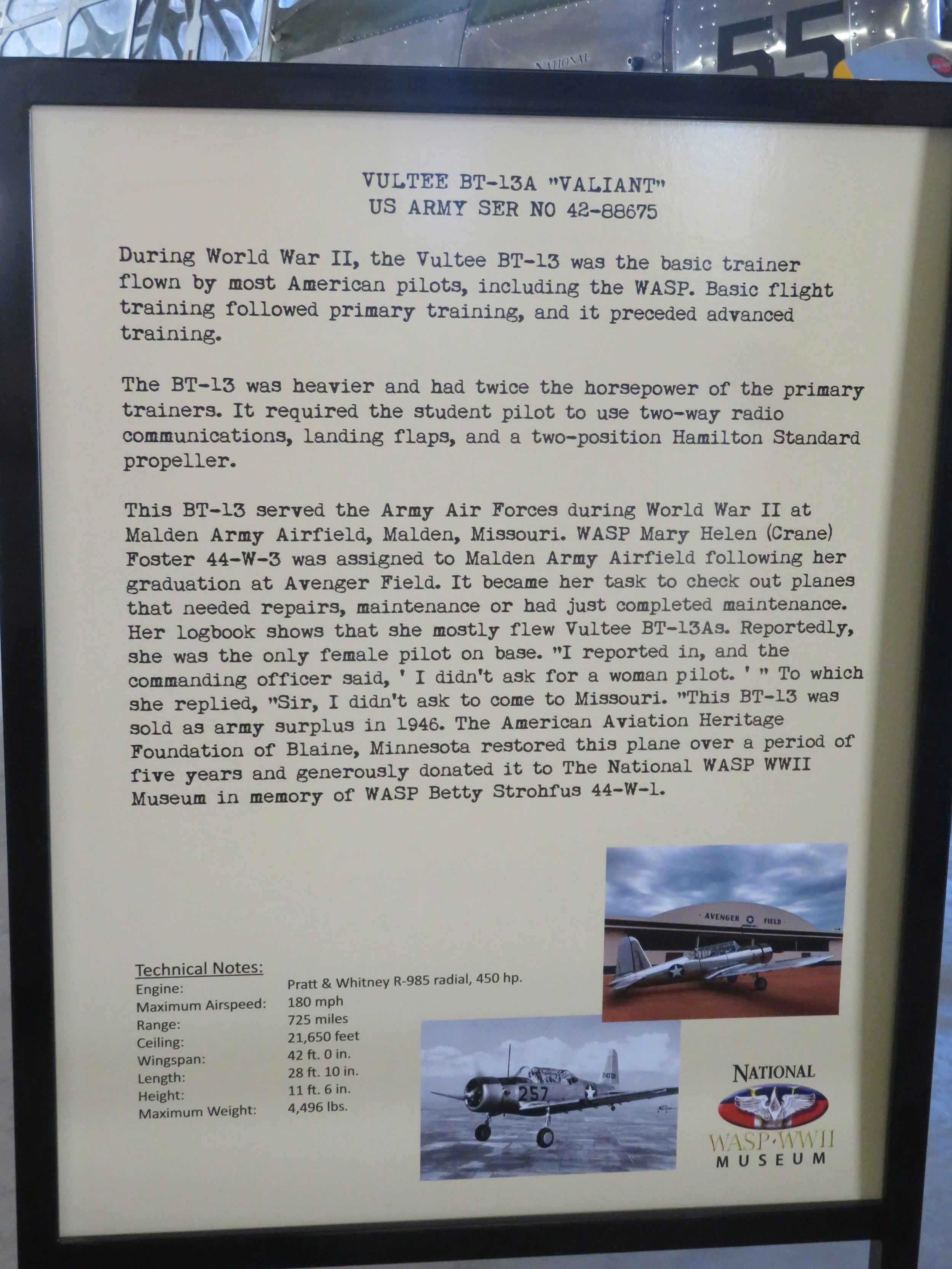

Basic Training – 70 hours flying BT-13s and BT – 15s, heavier, faster trainers.

The BT-13A

Advanced Training A – 50 hours flying AT-6s and AT-7s, a more advanced trainer with features such as retractable landing gear, larger engine, variable-pitch propeller and hydraulics.

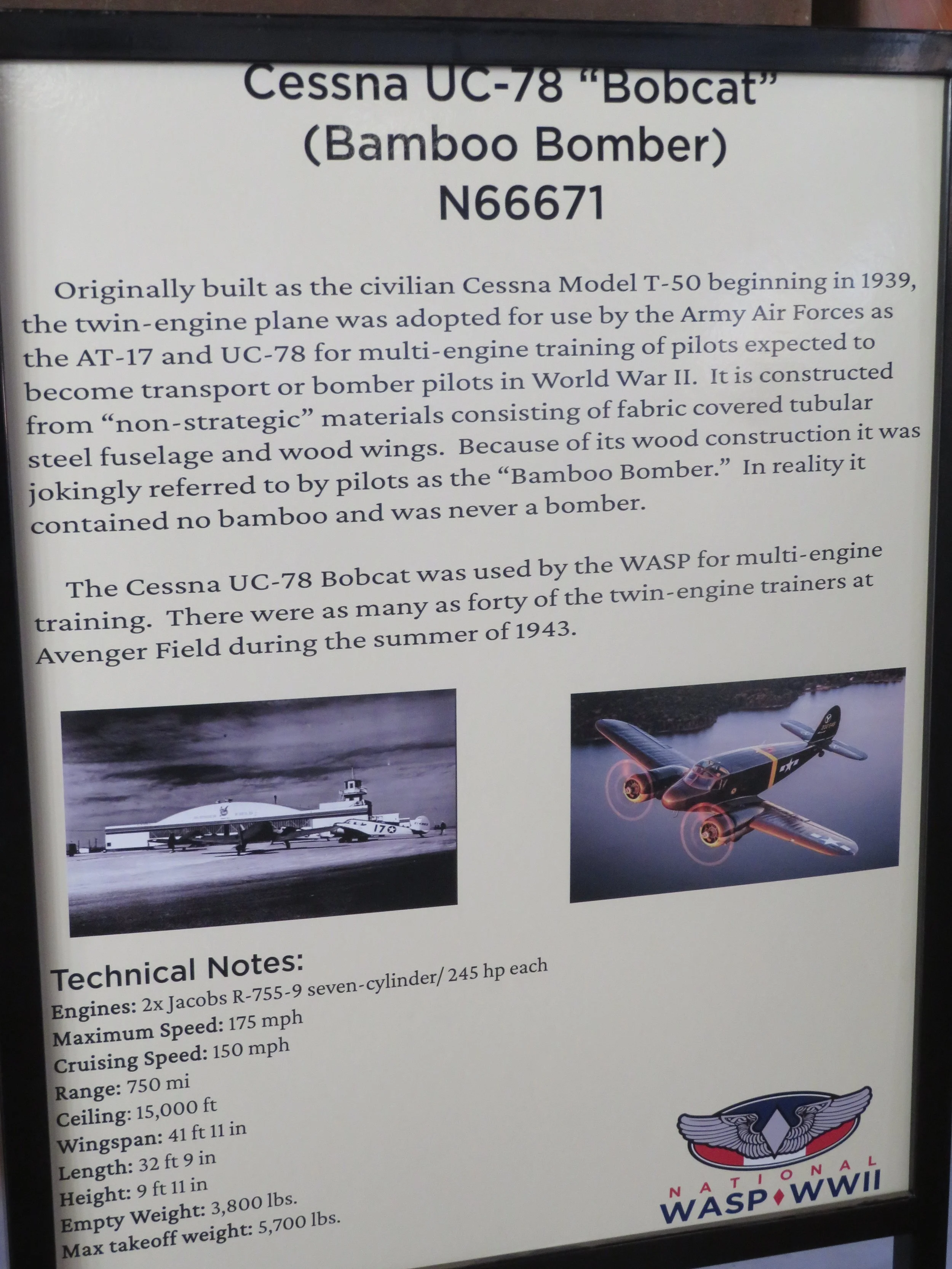

Advanced Training B – 20 hours flying UC-78s, an advanced mulit-engine trainer – made with bamboo wings!

The UC-78, a bamboo bomber

A cross section of the UC-78 wing with its bamboo struts.

After completion of each section, the women had to pass a flight test with an army pilot. If they passed, they moved on to the next section. If they failed, they washed out and went home. There were no mulligans nor “do-overs”, and since they were U.S. federal civil service employees, they had to pay their own expenses to get home.

Operation

When trainees graduated, they were assigned to over 120 bases throughout the country. Roughly 300 were assigned to ferry duty. Others became tow target pilots for gunnery practice… the women would tow targets with their planes while combat troops practiced firing with live ammunition. Some graduates were assigned to the glider training base in Lubbock while others were sent for training to fly B-17 and B-24 bombers.

Thirty-eight were killed in service. When a fatal crash happened, since they weren’t military pilots, the government did not pay for transportation or burial of the remains. Their fellow WASP would take up a collection for the funeral expenses and provide an escort to accompany the body on its trip home.

One ironic death occurred when a newbie male pilot was showing off and buzzed a good-looking WASP ferrying a newly built fighter. He flew too close to the WASP’s plane and clipped her wing with his landing gear, causing her to crash. The military ruled it an accident and there were no repercussions for the male pilot.

In total, there were eighteen graduating classes, and 1102 women became WASP. They flew over 66,000,000 miles in every type aircraft the military had including the fastest pursuit planes and fighters as well as the heaviest bombers and cargo planes. They ferried fifty percent of all the planes built during the war years.

An Ignominious Ending

In June of 1944, the House Commitee reported that it considered the WASP program unnecessary and unjustifiably expensive, and shortly after, a U.S. House bill that would have granted military status to the WASP was narrowly defeated.

In addition, during the height of the war, there were several civilian pilot training schools that provided the basic training for military pilots. By 1944, the war was beginning to wind down and there was actually an excess of military pilots. Since these schools were no longer needed, the civilian trainers would lose their draft deferments and they’d likely be drafted into the infantry. To prevent this, they formed a group that lobbied Congress in an effort to terminate the WASP program and use them instead.

Finally, Cochran had been pushing for military status for the WASP, and delivered an ultimatum – either commission the women or disband the program. Since funding for the program had to be approved by Congress, which was looking unlikely, and since there was very little likelihood of Congress granting military status, General Arnold ordered the program to be disbanded as of December 20, 1944.

Some of the WASP were allowed to travel home on government planes, but for the most part, they had to pay their own expenses from wherever they happened to be on Dec. 20.

Even though the WASP were never given military status, the program itself was considered a military operation, and all records were filed away as classified documents. It was never highly publicized, and most of the general public at the time was never even aware of the program. Within a few years, the entire WASP program was pretty much forgotten by anyone not directly associated with it.

Final Recognition

When women were going to be admitted to the military academies for the first time in 1972, a government spokesperson stated that these cadets would be the first women to fly military aircraft. Several surviving ex-WASP pilots pointed out that this wasn’t the case at all, and soon after, began fighting for veteran status. After a five-year struggle, a bill passed Congress and was signed into law by Jimmy Carter in 1977.

In 2010, the WASP received the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest honor Congress can bestow for distinguished achievements and contributions by individuals or institutions. The WASP were the third group to be recognized this way... the first was the Tuskogee Airmen and second was the Navajo Code Talkers.

It took only 66 years for the WASP to receive recognition for their contribution

For more information on the WASP, a quick Google search will provide a plethora of additional material. Coincidentally, I just happened to be reading a book by Fannie Flagg, The All Girls’ Filling Station Last Reunion, which devotes a good part of the book to a fictionalized account of one of the WASP pilots.

See you next week...