St. Thomas – Lake Mead’s Ghost Town Uncovered

/Recently I wrote about shrinking Lake Mead. The drought and the fact that the lake is shrinking are of great concern, but the discoveries since the water has diminished have been interesting and sometimes quite gruesome. Several bodies have been recovered and boats, sunken and lost decades ago, have now been found. Beyond the bodies and the boats, St. Thomas, the tiny community that was flooded in 1938 when the lake was formed is now dry once again and we decided to visit.

We took the long route around the lake, its ‘bathtub ring’ so very evident, accentuates its low level.

The final three miles to St. Thomas is accessed via a winding, dirt road.

There’s not much left of the town other than foundations and rubble after so many years of submersion, but the National Parks Service has done a great job with illustrated signage pointing out what was where and how this LDS/Mormon community operated ‘in the day’.

We descended a slight hill along a dusty, dirt trail and continued along a rock-lined path to the ghost town.

One notable and surprising observation en route was the number of clam shells we spotted along the trail. Through a little research, I learned the shells are a type of Asian fresh water clam (Corbicula fluminea) first recorded in North America in the 1930s and thought to have been accidentally introduced to Lake Mead back in the 1960s. The clams obviously thrived… at least when they had water.

A little history… from https://timetraveltrek.com/ghostly-remains-st-thomas-nevada/)

In 1865, Thomas Smith and a small group of Mormon men and women traveled through the area and, at the request of Brigham Young, worked to establish a settlement along the Colorado River to Salt Lake City freight route. They settled near the confluence of the Virgin and Muddy Rivers ~23 miles north of the Colorado River.

They were an industrious and innovative community and together they built an irrigation system to bring water from the Muddy River to their crops of cotton and grain. Vegetables and fruit trees grew and thrived in the fertile valley soil. By 1869, the irrigation system was extended with concrete-lined canals and ditches to the town, filling cisterns that became social hubs where residents came daily for buckets of water.

Believing they were either in Utah or Arizona, the group was dismayed when a survey determined they were actually in Nevada and were delinquent in back property taxes. They refused to pay and pretty much abandoned the town.

A few years later, another group moved in and, taking advantage of the previous group’s hard work, re-established the town along what became known as the Arrowhead Trail. The Arrowhead Trail was a "grassroots" effort including promotion by the various Chambers of Commerce and volunteer construction by local citizens. Because it stayed at a lower elevation, it was the first all-weather route between Los Angeles and Salt Lake City.

St. Thomas became an important stop on The Arrowhead Trail.

The task of maintaining it, however, often fell to the local residents. They agreed to rake more than 100 miles of this dirt road to keep it in good condition throughout the year. Because of St. Thomas’ location along the route, keeping the road open allowed the local economy to prosper. St. Thomas became a major stop and welcome oasis in the desert as the era of automobile travel blossomed.

It was Charles H. Bigelow, from Los Angeles, who gave it great publicity. During 1915 and 1916 he drove the entire route many times in his Twin-Six Packard "Cactus Kate."

As the town grew, mining became an important part of the town’s industry. In 1911, a railway spur line was constructed between Moapa and St. Thomas. When completed, railroad cars arrived full of commercial goods and even blocks of ice hauled in refrigerated cars. On the return, cars were filled with copper, silver and gold ore as well as salt, sand, fruits and grains.

The main street was lined with shaded trees, stumps of which still remain along the side of the trail.

At its peak, St. Thomas was home to almost 500 people. A 2-story, 4-classroom school was built for elementary age children while high school kids took a bus to Overton.

All that’s left of the St. Thomas school now is a crumbling foundation and a set of steps at the entry.

The Gentry Hotel, a 14-room establishment, provided accommodations to travelers and once hosted governors, senators and even President Calvin Coolidge.

The Gentry Hotel once stood here.

There were two grocery stores, a gas/repair station and even an ice cream parlor. It is the chimney of the ice cream parlor that is now the highest point in the town. At one time, however, it was 60’ under water

Unfortunately for St. Thomas, in 1928, President Calvin Coolidge signed a bill authorizing the building of the Boulder Dam, which would later be renamed the Hoover Dam. The forming of Lake Mead would flood the town and as a result, St. Thomas residents had no choice but to leave.

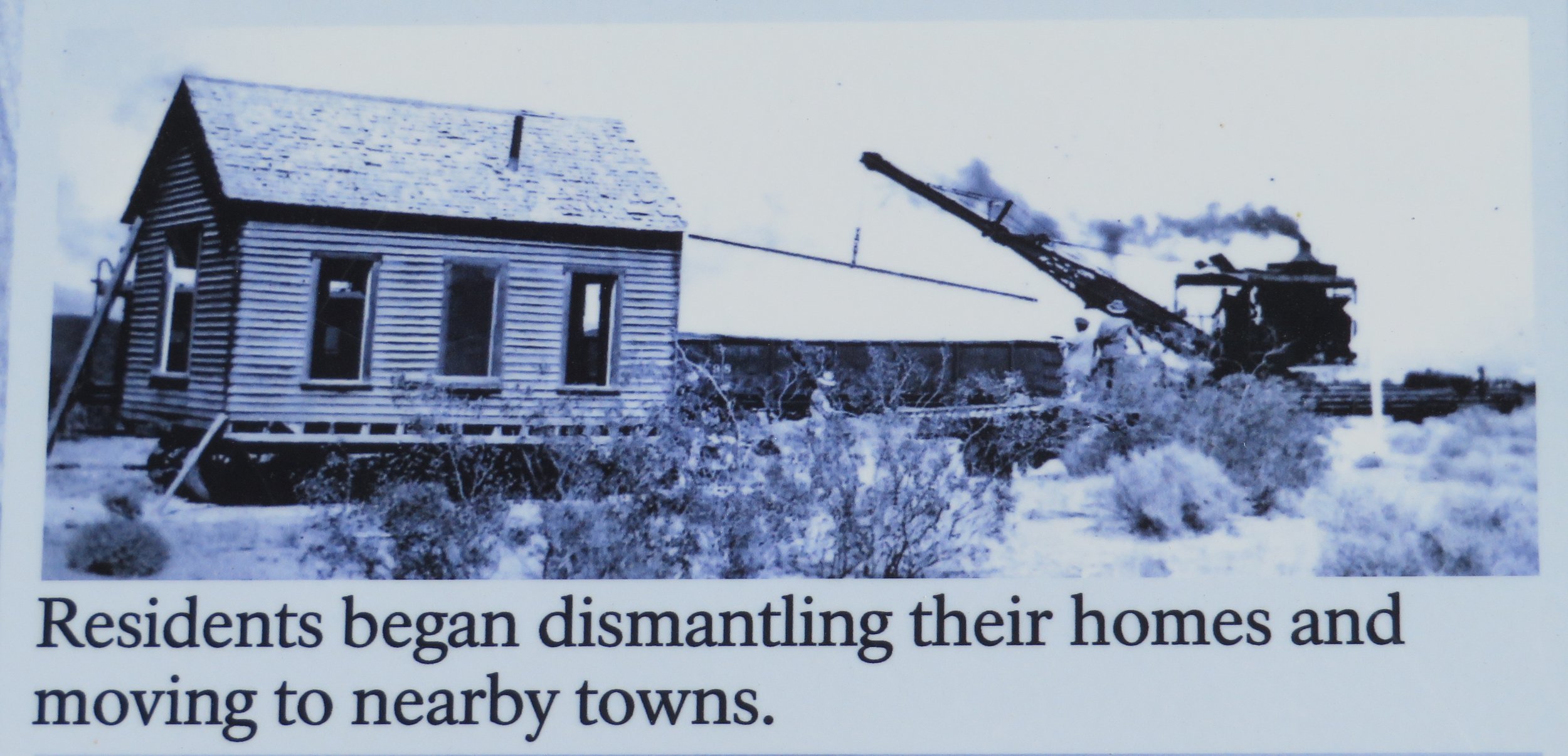

The government took over the land by eminent domain and residents were paid minimally for their land. Some residents chose to dismantle and move their houses.

Others just abandoned their homes. By 1932, only a few residents remained and the town was gone. By 1935, the filling of the lake commenced and took three years to fill. The last resident, Hugh Lord, burned down his house when the water reached his doorstep, then rowed away.

Senator Berkeley Bunker - Photo credit: LV Review Journal

Over the years, the lake’s water level has fluctuated and the town sometimes became visible again during unusually dry seasons. On those rare occasions, former residents and their descendants would meet at the site of the town and hold a reunion and ceremony. Reunions were held at St. Thomas in 1945, 1965 and 2012.

During the 1965 reunion, former Nevada Sen. Berkeley Bunker wore a battered old felt hat, which he said he had buried near his house in St. Thomas in the 1930s as Lake Mead was rising. He dug it up on the day of the 1965 reunion and plopped it on his head. In actuality, most of the town has been above the water since 2004.

When we visited, not only is the St. Thomas above water, we couldn’t spot even a glimpse of the lake from the town. It is dusty, dry and flat. The wind blew dust as we walked the trail and other than the old foundations and the NPS signage, there’s not an inkling that a prosperous town had ever existed here.

Walking around this ghost town, it was hard to believe that this parched piece of brown land was once a thriving, prosperous community. However, we did learn about the Arrowhead Trail and now our interest is piqued to find out more about it and perhaps hike along the route some time. Always a thread of information that makes us search for more. So much to explore and so little time.