Blue View - The Building of the Alaska Highway

/Now that we’re officially on the Alaska Highway, I thought I’d talk about what an amazing feat it was to build. In just eight months, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the entire 1,700 mile road stretching from Dawson Creek in British Columbia to Delta Junction in Alaska. Just the logistics and organization were staggering. The project required moving and organizing 10,000 soldiers and another 8000 civilian workers plus 250,000 tons (that’s 500,000,000 lbs!) of materials, supplies and equipment. It required the construction of 330 bridges - just counting the ones that were 20’ or longer. All that while encountering marshes, mountains, flash floods and bogs, and enduring swarming mosquitoes, and temperatures that dipped as low as -74°F. For an engineer whose largest project involved maybe 25 people, all working in pleasant, air-conditioned offices, the numbers involved and the conditions endured in the building of the Alaska Highway just boggle my mind.

Canada and the U.S. had been talking about building the highway since the 1920s, but despite several proposals back and forth, nothing had come of it. The attack on Pearl Harbor, along with Japanese threats to the Aleutian Islands and the west coast of the U.S. and Canada suddenly changed the importance of the road. It took just two months for Canada and the U.S. to agree to terms and for Congress and President Roosevelt to authorize it.

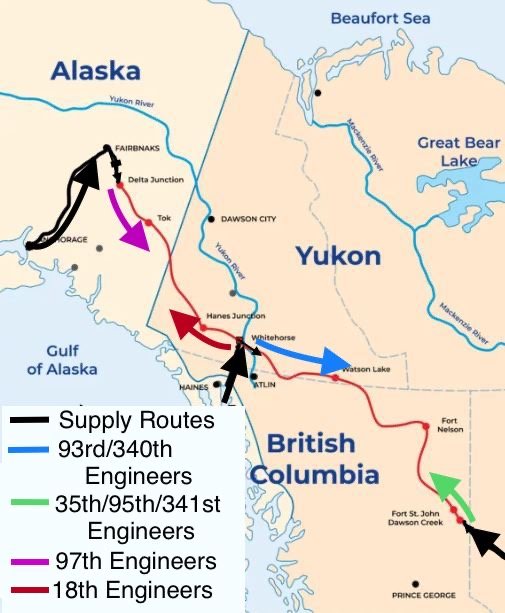

By mid-March, 1942, one month later, the basic route had been determined and the Army Corps of Engineers troops, along with materials, supplies and equipment had started to arrive. A total of seven regiments were sent. The plan was to start one group from the south at Dawson Creek, one from the north at Delta Junction, while two more groups would start in the middle at Lake Teslin. The army would build the basic “pioneer” road in 1942, then the U.S. Public Roads Administration (PRA) would take over and improve the roadway.

The surveyors led the way. They figured out the best path and marked it. These guys didn’t have the time to carefully analyze the terrain and pick the ideal route. Often, one of them would simply climb a tree and take a compass reading on a landmark in the direction they were headed, then climb back down and blaze a trail through the forest along that compass heading as best they could. Following close behind were three large bulldozers. The first one went along the centerline, knocking down trees and plowing out the beginning of the road. The next two bulldozers widened the roadbed to between 60’ and 90’. A number of smaller bulldozers came next, tasked with clearing the muck and debris. When a stream or river was encountered, a temporary pontoon or log bridge was constructed, allowing the crews to continue until a more permanent bridge could be built.

The main working units came next. Their job was to create a passable road surface using graders, loaders, scrapers, shovels and dump trucks. They sloped the roadbed for drainage and eliminated the steepest grades, added culverts, built more permanent bridges, and covered the surface with gravel. When marshy areas couldn’t be bypassed, they were either bulldozed down to firmer soil or built up using logs, then filled with soil and topped with gravel. Many of the equipment operators had no experience on anything bigger than a pickup truck, and learned on the job. At times, it got so cold, that the only way to keep transmission oil and gear grease from freezing when the equipment was left idle for an hour or two was to build a fire underneath using cans of used motor oil or fuel oil.

Many men, not used to the extreme temperatures, died of exposure. One truck with five soldiers aboard stopped at a checkpoint. The MPs discovered that while the three men in the cab were fine, the two in the covered rear, wrapped in jackets and sleeping bags had frozen to death. Sometimes when a vehicle broke down, the driver would freeze to death before help arrived.

On September 24th, the engineers working from both ends of the south half met at a stream they named Contact Creek, and on October 29th, the 97th and the 18th engineers met in the north section, completing the final link. The pioneer road was completed less than eight months after construction began. It was far from a usable supply road, however. About the only vehicles that could make the trip were 4x4s and 6x6 trucks. Some grades were as much as 24%! Cyril Griffith, a trucker who drove a tanker truck, remembers “Some of the steeper grades were up to 24% on the switchbacks. I have seen tools, chains, men and even trucks sliding down faster than a man could run." One particularly steep grade was named Suicide Hill. It had a sign at the top with the inscription “Prepare to meet thy maker”. It was the cause of several wrecked vehicles and at least one fatality.

The next spring, several bridges washed out and a number of sections became impassable due to flooding, and it became the PRAs job to make the repairs and turn the pioneer road into a usable military supply route. It employed more than 14,000 civilian contractors in 1943 improving the road and building permanent bridges.

After the war, the Alaska Highway was turned over to Canada. One article I read indicated that we gave it to Canada in return for allowing us to build a military supply route through their land, while another said that Canada took possession in return for half the cost of building it. Either way, it remained a military road for both countries until the fifties when it became a public road. I remember talking to several people, including my stepdad, who drove it in the fifties or sixties. It was still a gravel road then, and broken windshields and headlights, as well as flat tires were common. Now it is a two to four lane, paved highway.

Some statistics…

Cost for the Pioneer Road: $19.7 million (about $243 million in today’s dollars)

Cost for the PRA in 1943: $135 million (about $1.7 billion in today’s dollars)

Equipment used:

Bulldozers - 904

Dump trucks - 2790

Trucks (other) - 2374

Graders - 374

Shovels - 174

Scrapers - 370

Other - 4121

Equipment abandoned and left behind:

A lot. We see many rusted out WWII vintage vehicles adorning farmyards and businesses along our route. I saw one vintage WWII ambulance just outside Whitehorse that would have made a really cool camper conversion, if anyone’s interested. Just a little Bondo, some paint, new upholstery, an engine, transmission and drive train, tires and a few other minor items and it will be ready to start the camper upfit.

See you next week…