Blue View - The Chilkoot Trail

/

Imagine that it’s 1897. The country is in the middle of a recession, jobs are hard to find, inflation is rampant and unemployment is high. Then, the 60 point headline on the front page of every newspaper in the U.S. is “Gold Strike in the Klondike!”, followed by articles describing how gold nuggets are lying in the river beds, ready for the taking, and how this may be the richest strike in North American history. It doesn’t matter whether you are the ne’er-do-well son of a wealthy businessman, a carpenter having a very tough time keeping your wife and five kids fed, a card shark and con-man, or anyone in between, the lure of a great adventure and the dream of finding fabulous wealth might prove irresistible. It certainly was for an estimated 100,000 gold seekers who joined the greatest gold stampede in history.

There were several ways to get to the Klondike and start filling your pockets with some of those gold nuggets. The fastest, but most expensive was the “rich man’s route”. This route was entirely by ship, up the Alaska coast to the mouth of the Yukon River, then up the Yukon to Dawson City. The least expensive, but slowest route was to walk one of the overland trails. This was obviously very arduous, fraught with all sorts of dangers, and might take two years.

The most direct way to get to the Klondike, however, was to make your way to San Francisco or Seattle, either overland, by horse or train, or by boat, maybe sailing around the horn if you were starting from the east coast. From there, you’d find passage on a steamship heading to Skagway or Dyea, two neighboring towns in Alaska. Then, if in Skagway, you’d climb over White Pass, or if in Dyea, you’d go over the Chilkoot Pass. The Chilkoot Pass was shorter but steeper, while the White Pass was longer but easier. Once over either of these passes, you’d make your way to the Lakes Lindeman and Bennett, which form the headwaters of the Yukon River. There you would build a boat sturdy enough to carry you and all your gear 500-600 miles downstream, through several rapids, where you’d finally arrive in Dawson City. An unbelievable 20,000-30,000 gold seekers chose the Chilkoot or White Pass routes in just the first year of the stampede, most of them during the winter of 1897-1898!

To make the ordeal a little more interesting, there was a teeny, tiny additional complication. The Canadian authorities were fearful that many of those thousands of gold seekers headed their way, most of whom were inexperienced city folk, would die of exposure or starve to death. To prevent this, they required each stampeder to have the basic tools and gear to survive the trip, plus a year’s worth of food. That meant that each man had to haul about a ton of food and gear over the pass and on to the lakes. (At the end of the blog, I’ve included the list of items required.) The Canadians set up checkpoints at the border, which they declared as the top of each pass, to ensure the gold seekers had the requisite supplies… then charged duties on the imported goods.

The Chilkoot Pass was too steep for pack animals, so all the goods had to be hauled on someone’s back. That meant making between 25 and 40 trips over the pass and on to the lakes. The local Tlingit people, seeing an opportunity to make the best of a bad situation, hired themselves out as porters, charging by the pound to haul goods over the pass, but the majority of goods were hauled by the stampeders themselves.

(An aside here… I have a question regarding the logistics. Say you were a hale and hearty young man and could carry an 80 pound pack over the pass. How would you, along with those thousands of others, make 25 trips hauling loads of expensive, hard-to-get stuff from a cache at the bottom of the pass to another cache at the top, then to various caches en route to the lakes, without some serious issues with pilferage and outright theft? Were there guards available for hire? Did some enterprising sort set up guarded storage areas along the route? Did the men team up with four or five others so they could take turns guarding each cache? Or was everyone so honest and honorable that as long as you marked each cache with your name, no one else would bother it? I’m guessing it wasn’t the latter…)

Pack animals could be used on the White Pass, but the trail was so difficult, conditions so harsh and the prospectors so hard on them that more than 3000 animals died on the trail. Many of their bones lie at the bottom of the aptly named Dead Horse Gulch.

The entire Chilkoot Trail was only about 35 miles, but it was a very difficult 35 miles. It took an average of three months for each would-be prospector to haul all his food and gear from Dyea or Skagway to the lakes. To quote the National Park Service, “There were murders and suicides, disease and malnutrition, and deaths from hypothermia, avalanches, and possibly even heartbreak”. The Chilkoot Pass was at about the halfway point of the trail. Within sight of the summit were The Scales, a weighing station that weighed each man’s load before they could proceed to the top of the pass and the Canadian border. The Scales boasted six restaurants, two hotels and a saloon.

Following The Scales were the infamous “Golden Stairs”, a half mile, 1000 foot incline to the summit, so called because of the steps that were chopped out of the snow and ice by the prospectors. The thought of making 25-40 trips up the Golden Stairs was so daunting that many stampeders gave up and turned back, often leaving their required ton of goods at the base.

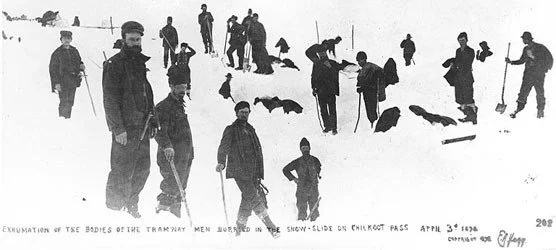

The deadliest event of the entire Klondike Gold Rush occurred on April 3, 1898 on the trail leading up to The Scales. Heavy snow had accumulated on the higher slopes over the winter which became very unstable when the first days of April brought warm southerly winds. The Tlingit porters refused to pack into the area and warned the stampeders of the likelihood of avalanches, but most ignored the warnings and continued carrying their goods up the trail.

On the night of April 2, several avalanches tumbled down the slopes above The Scales, burying 23 stampeders. Amazingly, all were rescued, but the threat of more avalanches convinced everyone in The Scales vicinity, some 220 people, to evacuate. The next morning, Palm Sunday, a snowstorm created whiteout conditions as all 220 started down the pass. They divided up into two groups, 20 in the first, and 200 in the second. Because of the low visibility, each group held onto a long rope to keep together.

Between 10:00 a.m. and noon that morning, three fatal avalanches occurred. The first killed three men who were camped further down the trail as they sheltered in their tent. The second killed all of the men in the first group descending from The Scales. The third avalanche buried half of the second group. News of the disaster soon reached the camps below, and within an hour or two, 1500 stampeders were digging frantically, trying to save as many victims as possible.

Over the next four days, the rescue efforts changed to recovery work. A large tent was set up to store the bodies until they could be identified and buried. Because so many were transients and because some of the remains were sent home or buried elsewhere, there was no accurate count of how many actually died, but the best estimate was 65. Most were buried in a small cemetery outside the town of Dyea.

One story has it that the local crime boss and conman, Jefferson “Soapy” Smith, offered his ‘help’ by appointing himself coroner, then had his gang members strip the bodies of any money and valuables.

It’s unknown how many of those 20,000 to 30,000 stampeders that arrived in Dyea and Skagway that winter survived and completed the trip to Dawson City and the Klondike, but they didn’t begin arriving until the summer of 1898. That was almost two full years after the first gold was discovered there, and by then, all the gold bearing areas had been staked and claimed, leaving no riches for the newcomers. Some stayed and worked the mines for others until the next gold strike in Nome, on the west coast of Alaska, a year later. Others returned home, broke and broken-hearted.

Later in 1898, the White Pass and Yukon Route (WP&YR) railroad was completed between Skagway and Whitehorse. This ensured Skagway’s future as a port city, while Dyea quickly faded away. The old townsite is now recognized as a National Historic Landmark even though there is hardly any evidence that the town ever existed.

The Chilkoot Trail is now jointly maintained by the Canadian and U.S. Parks Services. Until recently, it was possible to hike the entire trail, from Dyea to Lake Bennett. The trail now has several established campgrounds and warming huts. When it was open, park rangers were on duty throughout the summer to keep backpackers aware of weather and trail conditions. Extensive flood damage occurred in October of 2022, however, and only the first 1.5 miles are now open on the Alaska side. The portion of the trail north of the pass in BC can still be hiked by taking the historic WP&Y railroad to the ghost town of Bennett, and starting at the terminus of the trail at Lake Bennett.

While we were visiting the old townsite of Dyea, we hiked about a half mile section of the trail. We found it to be on the strenuous side; steep with lots of ruts, roots, gullies and boulders to scramble over. We wanted to experience it the way the old stampeders did, of course, so we were carrying our backpacks loaded up with 80 pounds of rocks. Would you believe 25 pound packs? Okay, okay - Marcie was carrying her camera with an extra battery and I had a water bottle.

See you next week…

P.S.

The following is a list of the food and gear required to by each prospector before they were allowed entry into Canada. The total weight was about one ton.

150 lb bacon

400 lb flour

25 lb rolled oats

125 lb beans

10 lb tea

10 lb coffee

25 lb sugar

25 lb dried potatoes

2 lb dried onions

15 lb salt

1 lb pepper

75 lb dried fruit

8 lb baking powder

2 lb soda

½ lb evaporated vinegar

12 oz compressed soup

1 can mustard

1 tin matches

Stove

Gold pan

Set of granite buckets

Large bucket

Knife, fork, spoon, cup, and plate

Frying pan

Coffee and teapot

Scythe stone

Two picks and one shovel

One whipsaw

Pack strap

Two axes and one extra handle

Six 8-inch (200 mm) files and two taper files

Draw knife, brace and bits, plane and hammer

200 feet three-eights-inch rope

8 lb of pitch and 5 lb (2.3 kg). of oakum

Nails, five lb each of 6,8,10 and 12 penny, (for four men)

Tent

Canvas for wrapping

Two oil blankets for the boat

5 yards of mosquito netting

3 suits of heavy underwear

1 heavy mackinaw coat

2 pairs heavy mackinaw trousers

1 heavy rubber-lined coat

1 doz heavy wool socks

½ doz heavy wool mittens

2 heavy overshirts

2 pairs heavy snagproof rubber boots

2 pairs shoes

2 blankets

4 towels

2 pairs overalls

1 suit oil clothing

Several changes of summer clothing

Small assortment of medicines