The Blue View - Latest and Greatest in Batteries Pt. 2

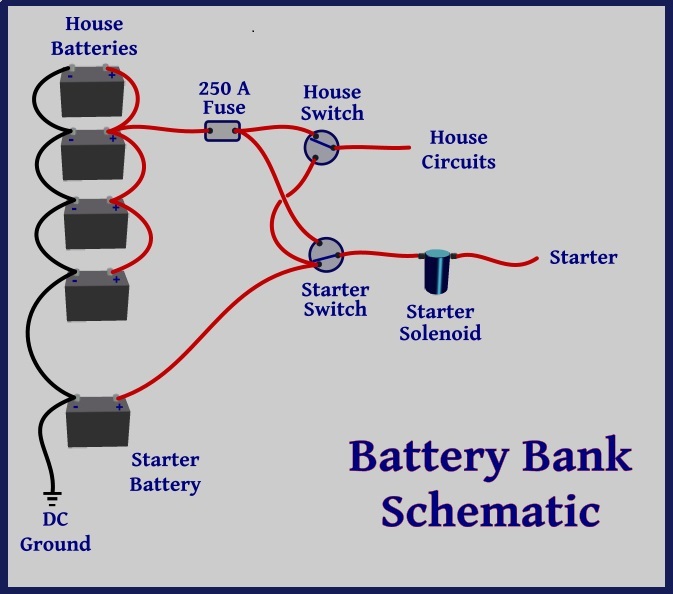

/ Boat batteries come in two basic types – starter batteries and house batteries. Starter batteries are designed to provide very large, short term current as the engine is started, then are recharged while the engine is running. These batteries are usually rated by their Cold Cranking Amps (CCA) - a measure of how many amps of current the battery can put out over a 30 second period without discharging the battery. For example, a battery with a CCA rating of 500 amps can provide 500 amps of current over a 30 second period in freezing temperatures and still maintain a voltage of at least 7.2 volts.

Boat batteries come in two basic types – starter batteries and house batteries. Starter batteries are designed to provide very large, short term current as the engine is started, then are recharged while the engine is running. These batteries are usually rated by their Cold Cranking Amps (CCA) - a measure of how many amps of current the battery can put out over a 30 second period without discharging the battery. For example, a battery with a CCA rating of 500 amps can provide 500 amps of current over a 30 second period in freezing temperatures and still maintain a voltage of at least 7.2 volts.

House batteries, on the other hand, are used to provide power for all the electrical equipment aboard, from the refrigerator to the laptop computers, and need to be recharged periodically. These batteries are designed to provide a much smaller current over a longer period than are starter batteries, and are rated by the number of amp-hours (ah) they can provide over 20 hours. Thus, a 200 ah battery can provide a constant 10 amps of current over a 20 hour period before becoming fully discharged.

The house batteries on Nine of Cups live most of their lives somewhere between ½ and ¾ full charge. Over the course of a day or two, the electrical demands of the boat slowly discharge them, but before they reach 50% of their full charge, we start the engine for an hour or two to recharge them. This never fully recharges the batteries – it would take several hours to totally top them off – but it does restore them to about 80% of full charge.

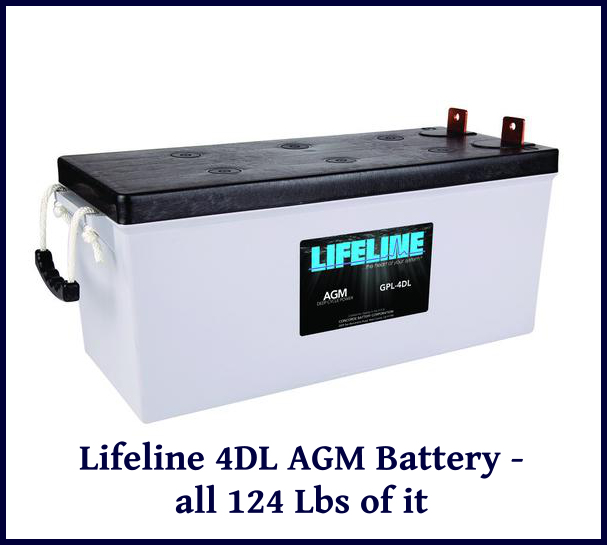

Almost every battery manufacturer will tell you this is a bad way to treat their batteries. They should always be recharged to full charge; otherwise the battery life will be much shorter than their normal expected life. Unfortunately, in the real world, this is how cruising sailboat batteries get treated. With our current Lifeline AGM batteries, I partially compensate for this mistreatment by running the engine long enough to fully recharge the battery bank at least once a month. In addition, after the first year or two, I found I needed to equalize the batteries once a quarter. (Equalizing is essentially a very controlled overcharging process that helps remove any sulfation build-up.) In evaluating batteries for a cruising boat, it’s important to consider how mistreating the batteries will affect the battery life, and the cost and time involved in compensating for the abuse they receive.

Since our house batteries are now about 8 years old (that’s about 120 in battery years), I am on a quest to find the best, most cost effective replacement batteries for Cups. So, what are my criteria for the ideal battery? Here is what I think is important – not necessarily in order of importance:

- Long life. Most battery manufacturers provide an important spec – how many times the battery can be recharged before it begins to lose its capacity. Usually, this is a function of how deeply discharged the battery is between recharges. A battery may be rated for 300 recharge cycles if it is always allowed to discharge to 25% of full capacity (Depth of Discharge or DOD) or 450 cycles if it is routinely recharged at 50% DOD (which is why we never let our house batteries discharge below 50% DOD). The more recharge cycles a battery is rated for, the longer its life will be. Depending on the battery type, the number of recharge cycles ranges from 100-200 cycles for an inexpensive battery to well over 4000 cycles for an expensive Li-Ion battery.

- High charging rate. The higher the charging rate, the faster a battery can be recharged and the fewer hours I’ll need to run the engine. This assumes, of course, that the charger – whether it is an alternator or a battery charger – can provide sufficient amps to take advantage of a high charge rate. An 800 amp-hour battery bank being charged by a 100 amp alternator won’t charge all that fast no matter what the maximum charge rate of the battery.

- Low actual cost. Obviously, the less they cost the better, but the true cost of a battery bank is much more than the initial purchase price. What does it cost to maintain them? How about the cost to keep them charged? What is the expected life? A battery that costs $250, but only lasts 2 years is more expensive over its life than a battery that costs $400, but lasts 6 years. There’s also the cost in time, effort and dollars, to swap out those four, 150 pound batteries, and recycle them – you can’t just toss them in the dumpster.

- Low maintenance. How much time is required to keep them maintained and to compensate for my mistreatment of them? Do I need to check acid levels every few weeks? Equalize them once a month?

- High level of safety. All batteries present safety issues. Wet cell lead acid batteries will boil off explosive hydrogen gas if overcharged and can spill acid if tipped over – both of which are possibilities on a sailboat. Sealed Gel and AGM batteries can generate hydrogen gas or can catch fire and burn if overcharged or charged at too high a rate. And we’ve all heard about the fire hazards lithium batteries pose if recharged incorrectly or are ruptured. All batteries present a risk of burns or fire if the terminals are shorted. So, in my mind, while there is no totally risk free battery, the ideal battery would be one that presents the least danger to the boat and crew.

There are a couple of additional things to consider before deciding on which batteries to buy. The first consideration is how many batteries are needed and how large they need to be. The process for determining this is to evaluate our electrical consumption over a 24-hour period. I’ll devote a future blog to this topic, but for now, we’ll assume our daily power usage averages 180 amp-hours. A good rule of thumb is to have a minimum of 3-4 times the daily electrical consumption in battery capacity, so we need batteries with a total capacity of at least 540 to 740 amp-hours.

Another very important consideration is how the boat is used. A sailboat that is used seasonally, maybe taken out for a couple of weeks during the summer and a dozen weekends throughout the year has much different requirements than a full-time cruising boat that spends very little time with shore power. In the first case, the batteries only see 10-20 recharge cycles every year, and even the least expensive batteries will last many years. In the latter case, the batteries may see 200-300 recharge cycles each year, and the less expensive batteries will likely only last a year or two. Thus, the ideal battery for one boat may not be the ideal battery for every boat.

So, let’s make some assumptions and estimates regarding our batteries to help in the selection process.

- Daily Power Consumption. We calculated our average daily power consumption to be around 180 amps. Some days will be considerably more (when we’re passagemaking and running nav instruments and the autopilot, for example), and some days less (when we’re ashore most of the day and not spending hours on the computers, writing blogs).

- Capacity. Most battery types will have a much longer life if we never let them get below 50% DOD. Therefore, we need at least 600 ah of battery capacity. If we are at anchor and want to do some inland travel for a couple of days, it would be nice to have enough reserve capacity to ensure the refrigerator will keep running while we’re gone, so let’s assume we would like at least 800 ah of capacity.

- Recharging. We have solar panels and a wind generator, which combined, average about 80 ah each day, and a shaft generator that puts out quite a bit of power – typically another 60 ah a day when we’re sailing. So, let’s assume we have to replenish around 100 ah per day using the engine. We have a 200 amp alternator, but unless we are running the engine at max rpm, it generates far less amperage than this. We typically run the engine at about 1500 rpm while recharging, which produces around 110 amps. Our engine consumes about 1.4 gallons of fuel per hour at this speed. Fuel prices around the world vary – ranging from $0.12 a gallon in Venezuela to more than $12 a gallon in St. Helena. In the U.S., let’s use an average of $2.50 a gallon for marine diesel, so it costs about $3.50 per hour to recharge at 110 amps per hour.

- Recharge cycles. We are sailing or on the hook about 75% of the time and are without shore power around 275 days each year. We don’t typically need to run the engine every day, so let’s assume we recharge the batteries from 50% DOD 200 days each year.

After all that preliminary stuff, it’s finally time to look at the battery choices. What I plan to do is to examine each type of battery chemistry, list the pros and cons of each, then evaluate the size, weight, number of batteries, purchase price and actual cost of each for our new battery battery bank.

Unfortunately, I’m going to have to put that off until next week’s Blue View – I’m still collecting data and specs from a few battery manufacturers. Stay tuned.

By the way, thanks to the several folks who commented or contacted me regarding battery information and ideas.