The Blue View - Docking with One Line

/Several years ago, I read an article in Good Old Boat written by Dave Chase. The article talked about tying up to a dock or jetty, at least temporarily, using only a single line. If done properly, the line can be dropped over a cleat using a boathook, and once in place, the boat is pulled into the dock as it motors forward. Then a crew member can step down to the dock and attach the remaining lines. We tried the method, tweaked it a bit for Nine of Cups, and found that it makes docking, whether in a slip or at a linear jetty, a great deal easier for a shorthanded crew. We now use this technique almost all the time.

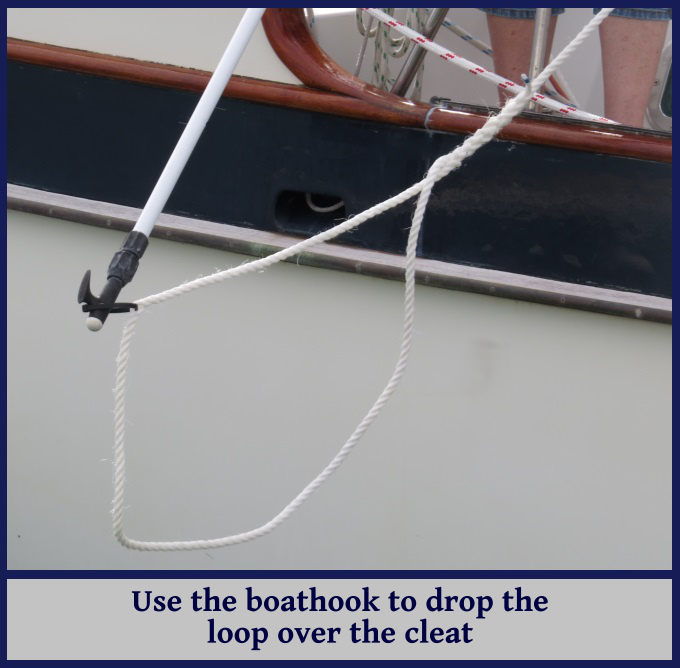

The method uses a single springline that is attached to a cleat on the dock, then run forward through a block at the boat's pivot point, and back to a cockpit winch. We use a 45' (14m) length of 1/2” (12mm) 3-strand polypropylene line for our springline. We have a large, three foot (1m) eye spliced in one end. Attached to the eye-splice is a small loop made from a cable tie. This small loop is just large enough to fit the end of the boathook.

As we approach the dock, Marcie rigs the springline so that the loop just reaches the stern of the boat. She routes the line so it passes through a block on the rail at a point just about even with our mast, then back to the cockpit, where it is secured to a winch. She stands at the midship gate, holding the loop with the boathook. As soon as the cleat is within reach of the boathook, Marcie drops the loop over a cleat. Then, I continue motoring forward slowly until Cups is pulled into the dock. Once the springline is tensioned, I keep Cups in gear and turn the wheel away from the dock. Depending on the wind, I may have to give us slightly more throttle to keep us at the dock. Then as long as we keep the engine running and in gear, Cups will stay nestled up against the dock, allowing us time to leisurely step down to the dock and attach the bow, stern, and normal springlines. Once securely tied, we shutdown the engine and remove the temporary springline.

Some experimentation may be needed to find the right spot to locate the block on the rail. If it isn't far enough forward, the bow of the boat will swing out.

When it is time to leave, we use one of several options. If we need to spring either the bow or stern away from the dock, we use the technique described in the earlier blog on springing off a dock. If all we have to do is motor forward or backwards, we reverse the process above. We attach the springline as before, start the engine, turn the wheel away from the dock and put it in gear. Then we can remove all the other lines leisurely and step back aboard. Marcie hooks the loop with the boat hook, and lifts it off the cleat as soon as I put the engine in neutral, taking the tension off the line.