The Blue View - Chainplate Issues

/The typical lifetime of the standing rigging on a sailboat is 10-15 years, while the typical lifetime for the chainplates is 20 years. We replaced the rigging in Colombia about 13 years ago, so it is now due to be redone. The chainplates, however, were never replaced, and are now well past their “use by” date. They are totally fiberglassed into the hull, making a thorough inspection impossible without removing a lot of interior cabinetry and grinding out large sections of the hull. I routinely inspect the exposed portions, and while they never showed the least sign of internal corrosion or water ingress, I knew we were sailing on borrowed time.

A few days ago, when I was doing our pre-passage rigging check, I noticed a salty, vinegar-smelling substance coming from the chainplate cover on one of the starboard shrouds – not a good sign. There was no doubt in my mind that it was now time to replace the old chainplates, and since the rigging was nearing the end of its life, I decided to replace it as well. In addition, if we were going to get everything done before our South African visas and the customs permit on the boat expired, we would have to hire the work out instead of doing it ourselves. This was going to be an expensive few weeks.

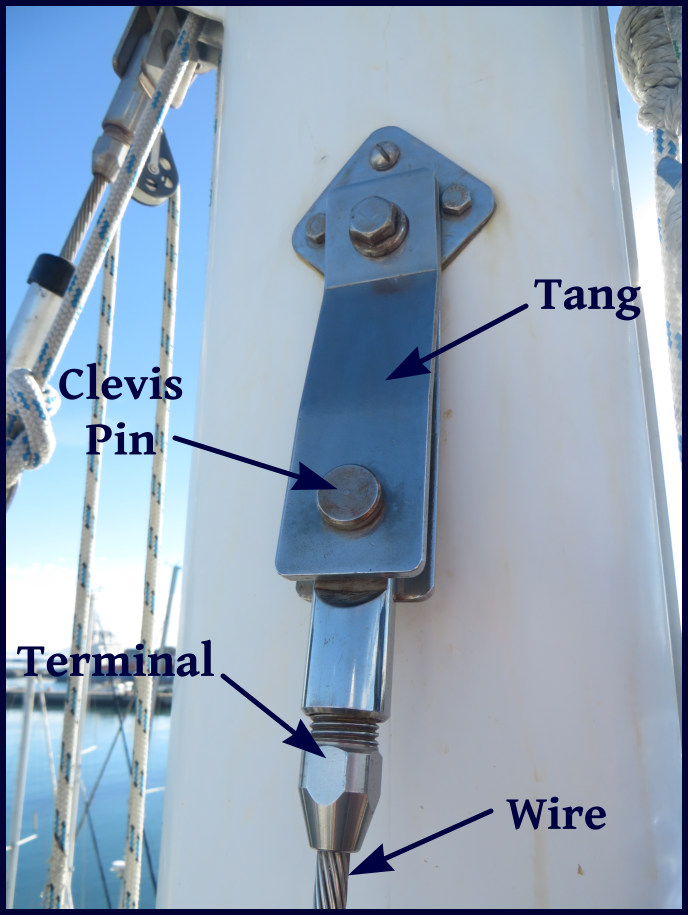

Because it was not feasible to remove and replace the old chainplates, my plan was to attach stainless straps to the outside of the hull. Holes would be drilled all the way through the hull and the old chainplates, and the straps attached to the hull using bolts secured on the inside with nuts and washers. I've seen this done on another Liberty 458, as well as several similarly designed boats. If the straps are polished, the bolt heads countersunk flush, and the carpentry done right, the end result is, hopefully, not only be strong, but attractive as well.

Cape Town is a great place to get boat work done. They have an active boat building business, and there are hundreds, if not thousands, of local boats, as well as many more boats passing through, all of which support a number of skilled marine tradesmen. Once the decision was made to replace the chainplates, I wanted the advice of experts to make sure I did it right. I talked with the local marine services expert, who quickly contacted a marine architect (to evaluate and design the chainplates), a rigger (to replace the standing rig), a stainless steel fabricator (to make the chainplates), a marine carpenter (to modify the cap rail, rub rail and interior cabinetry with minimal damage), and a shipwright (who will be drilling the holes). With all these experts, what could possibly go wrong?

Photos were taken and sent to the marine architect, and the various experts conferred with each other. A few days later, Dave, who owns the marine services company called to say the plans were done and the quote prepared. If I came by and signed off on it, we could get started. I checked the quote and the drawings, and thought the price was quite reasonable. But then I noticed there weren't enough chainplates in the quote – we need eight and there were only six in the quote. Dave thought about it, made a trip down to Nine of Cups, and agreed that the quote was wrong. He said he would get it redone and get back to me.

The next day Dave called again and said the quote was revised. I stopped into his office and looked everything over. The price, as expected, had gone up because of the added chainplates. In South Africa, as well as most of the world outside the U.S., everything is done in metric. I'm used to seeing things in millimeters and centimeters, but I still have to convert a dimension to feet and inches to get a feel for the size. While I was checking the drawings, I saw that they were 350mm long, and mentally estimated that that would be equivalent to about 13-14 inches. This just didn't seem long enough to me, so I asked for a copy of the drawing to take to the boat and make some rough measurements, just to convince myself everything was right. Sure enough, the chainplates were too short. Some of the bolts would have passed through the bulwarks instead of the hull, and two holes in each chainplate would have been drilled right into the deck.

Dave apologized again, and conferred with the marine architect who lengthened the chainplates and reworked the drawings. The new quote was considerably higher, and had yet another problem. The fourth quote appeared correct, but was just about double the first quote - not so reasonable anymore. I signed off on it and the stainless fabricator was given the go-ahead.

That was Thursday. Friday was a holiday, and on Saturday the carpenter stopped by. I told him about the lengthened straps, and he pointed out yet another problem. The hull has a small step just under the rub rail. It isn't obvious because the rub rail hides it. If the chainplates are lengthened, we will need a spacer behind each chainplate, which may or may not be a problem. Dave will need to check with the marine architect on Monday, and hopefully, the machinist hasn't started on the chainplates in case there is another change needed.

Other than that, everything is going just fine.