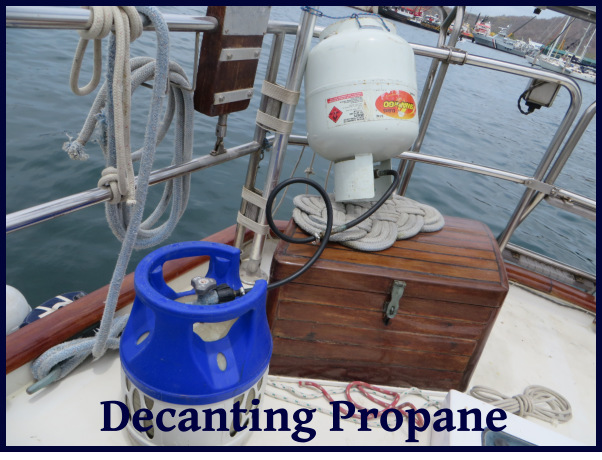

The Blue View - Decanting Propane

/ One of the chores to complete before leaving Trinidad was to fill our propane tanks. Running out of propane on a passage, while not exactly life threatening, would certainly be a hardship. Actually, if I went a few days without my morning coffee, the first mate might be ready to jump overboard - or throw me to the sharks – so, truth be told, it might very well be a life threatening situation.

One of the chores to complete before leaving Trinidad was to fill our propane tanks. Running out of propane on a passage, while not exactly life threatening, would certainly be a hardship. Actually, if I went a few days without my morning coffee, the first mate might be ready to jump overboard - or throw me to the sharks – so, truth be told, it might very well be a life threatening situation.

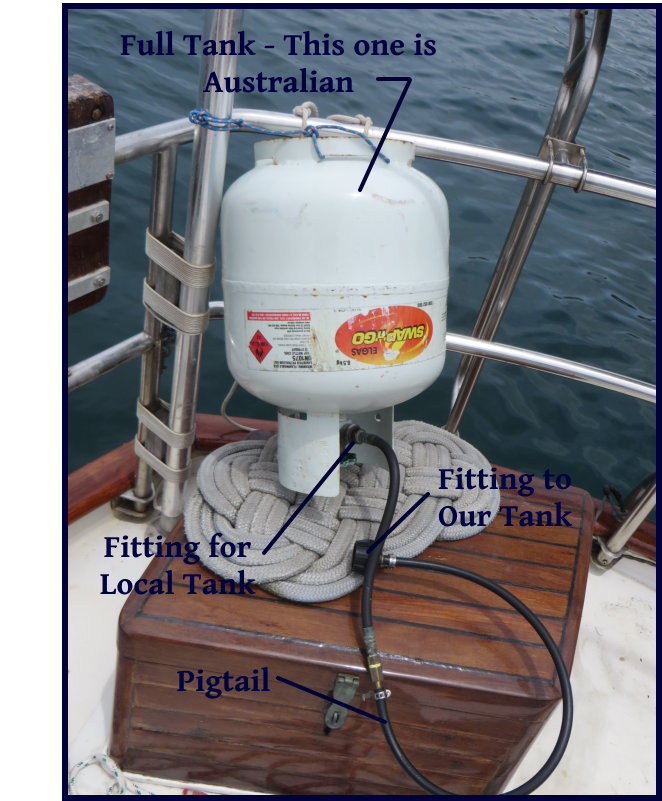

We have three tanks aboard Nine of Cups; two fiberglass 10 lb. (4.6 kg) tanks that fit down into our propane locker, and a standard 20 lb. (9.2 kg) steel tank that sits on deck inside a nice, made-to-purpose ditty bag. When one of the smaller tanks becomes empty, I refill it using the large tank.

In many parts of the world, it is expensive and/or quite difficult to get our tanks refilled. There are often places that will swap filled tanks for empties, or refill the local tanks, but just as often, either the tank fittings are different, or local codes prohibit the filling of any but their approved tanks, or there isn't a refill station within walking distance of Nine of Cups. So, we usually buy or borrow a local tank, and use it to fill our tanks.

Decanting propane isn't difficult. A full tank contains mostly liquid propane with a little propane vapor at the top. To move the liquid propane from the full tank to the empty tank, I connect the two with a hose, set the full tank upside down and higher than the empty and open the valves on both tanks. The liquid propane runs out out of the full tank and into the empty. That's the principle anyway – in reality there are a few complications.

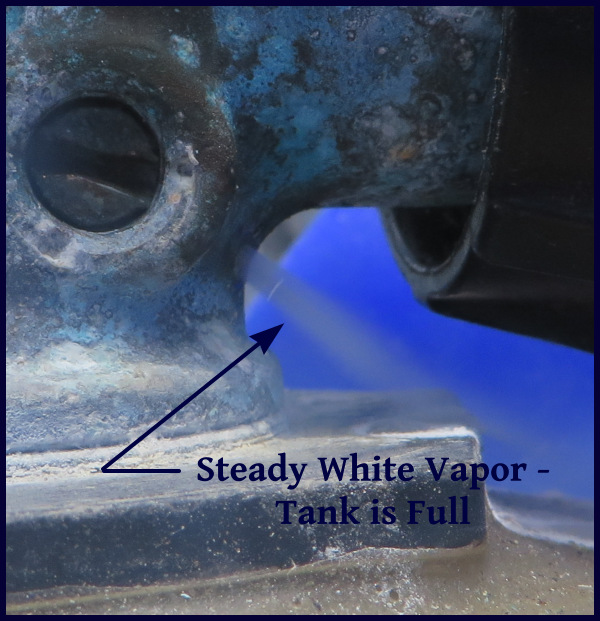

- The liquid needs a little help to flow into the empty tank once the vapor pressure builds up in the partially filled tank. Most tanks have a small bleed screw that allows the vapor to escape as the tank fills up. I can hear the flow of liquid as it moves from one tank to the other, and once I hear the initial flow of liquid slowing down, I loosen the bleed screw until the vapor begins to escape from the partially filled tank. I watch the escaping vapor - it will be clear with spits of white liquid until the tank is full. Once the tank is full, the escaping propane will turn white, and I know it's time to tighten the bleed screw. Some propane is lost using this technique. If there is no bleed screw or I want to avoid losing any propane, the liquid from the full tank will eventually fill the empty without loosening the bleed screw, but it sometimes takes 24 hours or so.

- When I set the full tank upside down, I keep it at a small angle rather than positioning it completely vertical. It likely has rust in the bottom which I don't want transferred to my tanks.

- If I am not using the bleed screw, before opening the valve on the empty tank, I loosen the connection between the tanks so any air in the line will be purged and not forced into the empty tank. When using the bleed screw, this step is unnecessary since air is lighter than propane and will be purged via the venting process.

- Many countries have a different fitting on their propane tanks than what we are used to in the U.S. It seemed like every South American country we visited had a different standard. Part of the adventure was visiting hardware and plumbing stores until I found a fitting (or combination of fittings) that would allow me to connect the local tank to the hose and pigtail connection for my tanks. I have a ditty bag chock full of adapters from around the world.

- I always secure the full tank in its upside down position so it can't fall over or overboard if there is an unexpected wake or surge.

- Propane is heavier than air, and any propane that leaks or is released inside the boat will collect in the bilge. If enough collects down there, an explosion and/or fire may result. We had acquaintances on a French boat that blew a hole in the side of their boat after a propane leak. The boat was partially sunk and the wife was badly burned. It happened in a remote part of Patagonia, and they spent a week or so surviving ashore until the Chilean navy found and rescued them. I always make sure any escaping propane vapor is blown overboard – or better yet, I do my decanting ashore when I can.

- Obviously, the escaping propane vapor is highly flammable – I make sure there are no open flames, sparks, etc. anywhere near.

Our three tanks give us enough cooking fuel for 3-4 months – a little less in the cooler climes when we bake more and a lot longer in the tropics when we avoid baking. We no longer have a BBQ grill which seemed to be less efficient. That's been enough propane to keep the crew happy between refill opportunities, whether a long ocean passage or extended gunkholing in Patagonia or the nether regions of Tasmania.

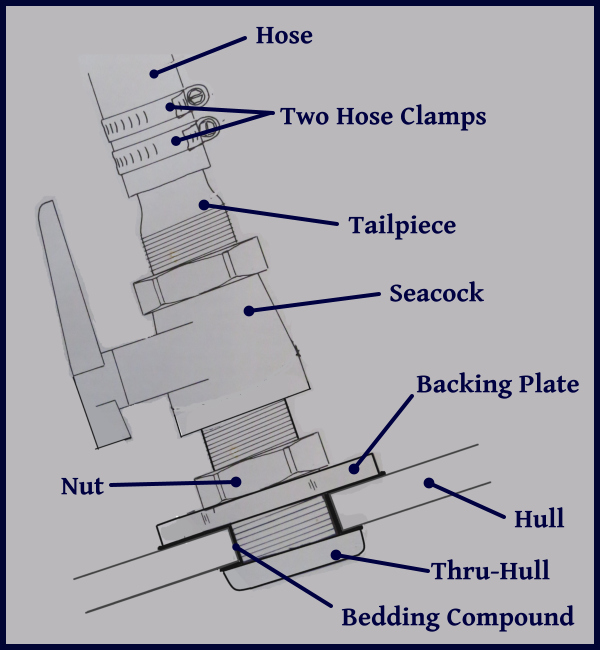

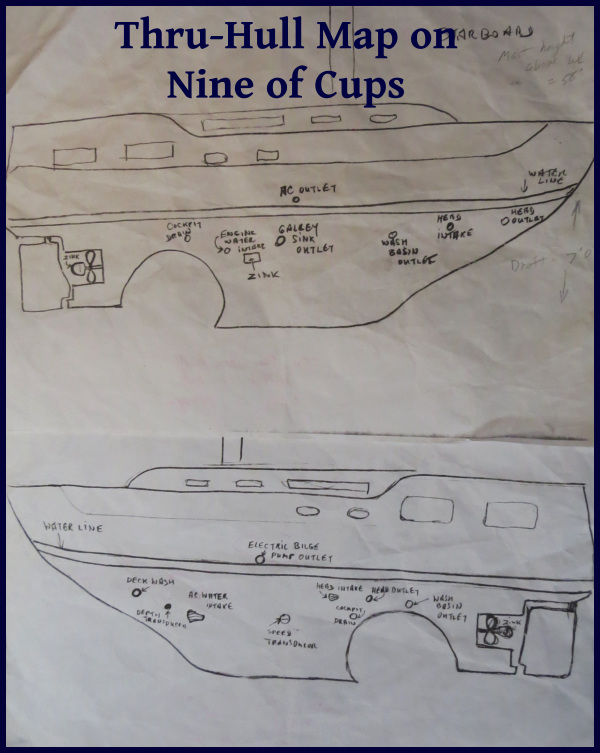

Nine of Cups has 16 thru-hulls – holes in her bottom. A couple of these are for depth and speed transducers, but 14 are used to allow water into or out of the boat. For example, one is used as an engine cooling water intake, another is connected to the galley sink drain, another serves as the water intake for our desalinator, and so on. Since it could be a real disaster if a hose connected to one of these thru-hulls broke or came loose, each of the 14 thru-hulls is fitted with a shut-off valve - or seacock in sailor's parlance. As part of our annual haul-out chores, we check, lube and exercise each seacock, and examine all the hoses and hose clamps.

Nine of Cups has 16 thru-hulls – holes in her bottom. A couple of these are for depth and speed transducers, but 14 are used to allow water into or out of the boat. For example, one is used as an engine cooling water intake, another is connected to the galley sink drain, another serves as the water intake for our desalinator, and so on. Since it could be a real disaster if a hose connected to one of these thru-hulls broke or came loose, each of the 14 thru-hulls is fitted with a shut-off valve - or seacock in sailor's parlance. As part of our annual haul-out chores, we check, lube and exercise each seacock, and examine all the hoses and hose clamps.

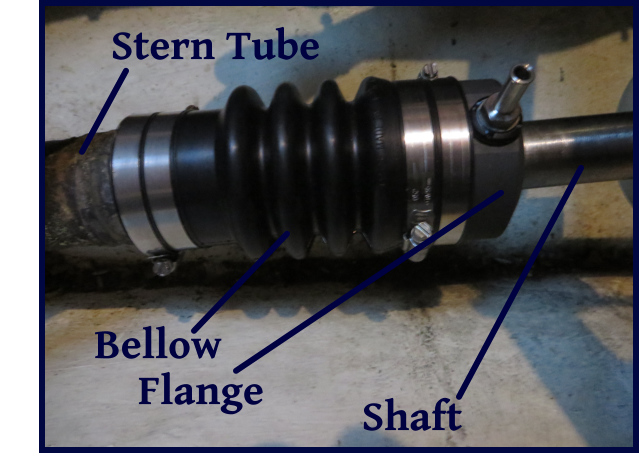

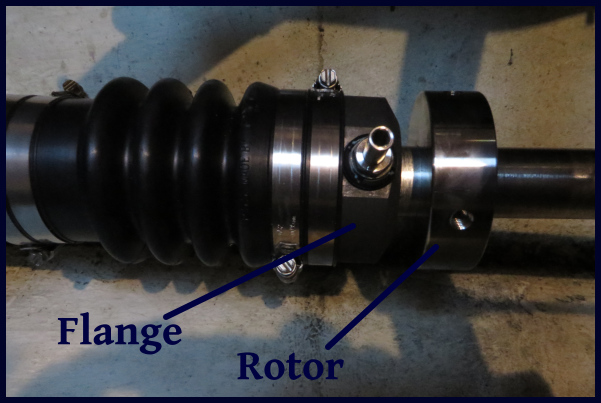

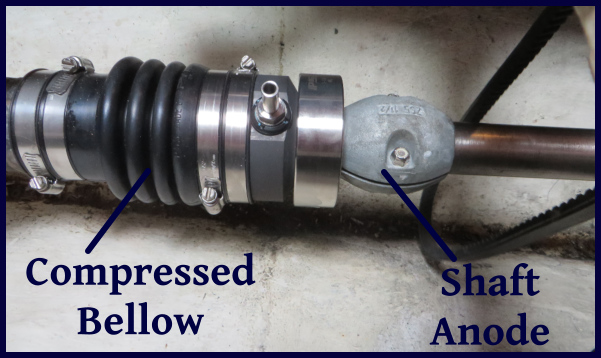

As part of the process of replacing the cutlass bearing, the old shaft seal had to be removed. I installed a 'dripless' shaft seal about 14 years ago, and while I've serviced it regularly over the years, I thought it might be a good time to replace it as well.

As part of the process of replacing the cutlass bearing, the old shaft seal had to be removed. I installed a 'dripless' shaft seal about 14 years ago, and while I've serviced it regularly over the years, I thought it might be a good time to replace it as well.